The Anunnaki are a fascinating group of deities that played a significant role in the mythology and religion of ancient Mesopotamian civilizations. Their origins, characteristics, and functions have intrigued scholars and sparked the imagination of those interested in ancient cultures. Let’s explore the history, mythology, and cultural significance of the Anunnaki.

Get your dose of History via Email

Origins and Etymology

The Anunnaki are gods from the ancient Sumerian, Akkadian, Assyrian, and Babylonian civilizations. The name “Anunnaki” comes from the Sumerian sky god, An, and the earth goddess, Ki. The name translates to “princely offspring” or “offspring of An.” In the pantheon of ancient Mesopotamian deities, the Anunnaki are seen as the descendants of An and Ki.

The Most Prominent Anunnaki Deities

Enlil: Enlil is the god of air and is often considered the chief god of the Sumerian pantheon. The Sumerians believed that heaven and earth were one until Enlil was born. Enlil separated them, carrying away the earth while his father, An, took the sky.

Enki: Also known as Ea in Akkadian mythology, Enki is the god of wisdom, water, and creation. He is often depicted as a benefactor of humanity, responsible for teaching humans the arts and crafts of civilization.

Inanna: Inanna, also known as Ishtar, is the goddess of love, beauty, war, and fertility. She is associated with the planet Venus and plays a prominent role in many Sumerian myths, including “Inanna’s Descent into the Netherworld.”

Ninhursag: Often identified with Ki, Ninhursag is the mother goddess. She is associated with fertility, birth, and the nurturing of life.

Utu: Known as Shamash in Akkadian, Utu is the sun god. He is associated with justice and often portrayed as a lawgiver.

Worship and Characteristics

The Anunnaki are primarily mentioned in literary texts, and there is little evidence of their collective worship. Instead, each Anunnaki deity had their own cult. Ancient Mesopotamians depicted these gods as anthropomorphic figures with extraordinary powers and immense size. They often wore melam, a divine radiance that inspired fear and awe.

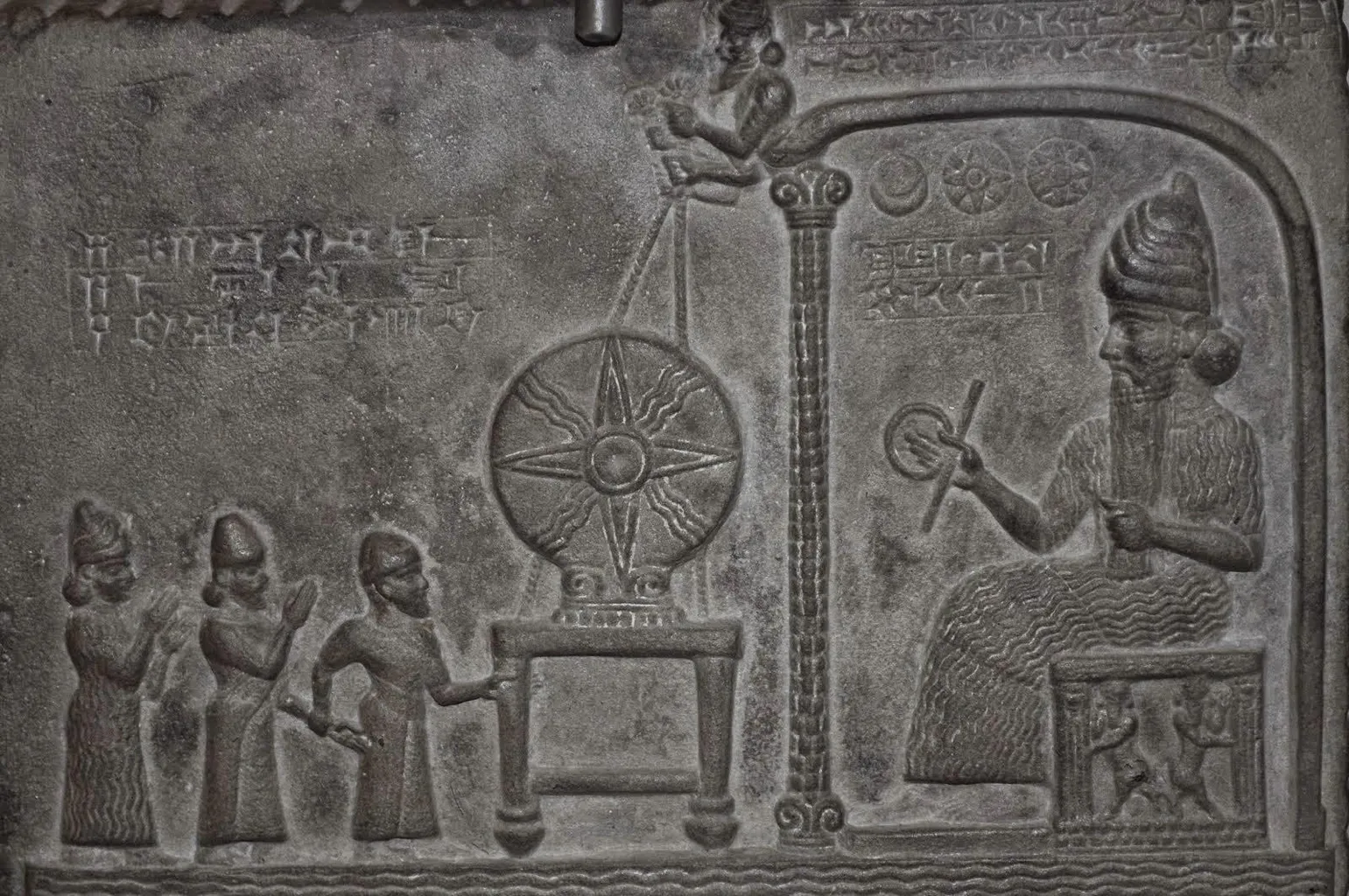

Iconography

Anunnaki deities were typically shown wearing horned caps with up to seven pairs of ox-horns. They wore garments decorated with gold and silver. Their statues, believed to embody the gods themselves, received daily care and offerings from priests. The temples served as their earthly homes, and each god had their own temple in the city they patronized.

The Assembly of the Gods

The Anunnaki participated in the “assembly of the gods.” This assembly mirrored the legislative systems of the Third Dynasty of Ur (c. 2112 BC – c. 2004 BC). It was a divine council where the gods made all their decisions. Each major city had a patron deity who protected the city’s interests. For instance, fifty Anunnaki were associated with the city of Eridu.

The Anunnaki in Sumerian Mythology

Roles and Functions

The Anunnaki’s roles and functions varied across different texts. In early myths, they were heavenly deities with immense powers. They played a crucial role in determining the fates of humans. The poem “Enki and the World Order” describes how the Anunnaki praised Enki and settled among the people of Sumer. They also had the power to decree the destinies of mankind.

Anunnaki as Judges

In some myths, the Anunnaki appear as judges. In “Inanna’s Descent into the Netherworld,” they reside in the Underworld and serve as judges over the dead. They try Inanna for her attempt to take over the Underworld, find her guilty, and condemn her to death.

Celestial Associations

Sumerians associated the Anunnaki with celestial bodies. Inanna represented Venus, Utu symbolized the sun, and Nanna (Sin) was the moon. An was linked with stars of the equatorial sky, Enlil with those of the northern sky, and Enki with the southern sky.

Anunnaki in Akkadian, Babylonian, and Assyrian Texts

Chthonic Deities

In Akkadian texts, the Anunnaki are often depicted as Underworld deities. For example, in the poem “Inanna’s Descent into the Netherworld,” Ereshkigal, the queen of the Underworld, drinks water with the Anunnaki. They are summoned to sit on golden thrones and adorn threshold steps with coral.

The Igigi and the Anunnaki

During the Old Babylonian Period (c. 1830 BC – c. 1531 BC), another group of deities known as the Igigi emerged. Their relationship with the Anunnaki is not clear. Sometimes, texts use these terms interchangeably. However, in the Atra-Hasis epic, the Igigi are gods forced to work for the Anunnaki. After forty days, they rebel, leading Enki to create humans as replacements.

Underworld and Cosmology

From the Middle Babylonian Period onward, the Anunnaki became associated with the Underworld. The Igigi were considered heavenly deities. In the Babylonian Enûma Eliš, Marduk assigns the Anunnaki roles. There are 600 Anunnaki of the Underworld and 300 of heaven, reflecting a complex underworld cosmology.

Epic of Gilgamesh

In the “Epic of Gilgamesh,” the Anunnaki are described as seven judges of the Underworld. They set the land ablaze as a storm approaches. When the flood comes, Ishtar and the Anunnaki mourn humanity’s destruction.

Anunnaki and Marduk

Marduk, the national god of Babylon, holds authority over the Anunnaki. In the Enûma Eliš, the Anunnaki build the Esagila temple in Marduk’s honor. In the Poem of Erra, the Anunnaki appear as Nergal’s brothers, portrayed as hostile to humanity.

Anunnaki in Hurrian and Hittite Mythology

Former Gods

In Hurrian and Hittite mythologies, the Anunnaki are identified as “former gods.” The younger gods banished them to the Underworld. These ancient deities were ruled by the goddess Lelwani.

Names and Functions

The Hurrians called the Anunnaki karuileš šiuneš, meaning “former ancient gods,” or kattereš šiuneš, meaning “gods of the earth.” Though the names varied, there were always eight Anunnaki. The Hittites and Hurrians swore oaths by these old gods for ritual purifications.

Similarities with Greek Mythology

The Hittite account of the Anunnaki’s banishment resembles the Greek poet Hesiod’s tale of the Titans’ overthrow by the Olympians. The Greek sky-god Ouranos mirrors Anu, the Sumerian sky god. Just as Cronus castrates Ouranos, Anu is castrated by Kumarbi in Hittite myths.

Anunnaki and Pseudoarchaeology

Erich von Däniken’s Theories

Erich von Däniken introduced the idea of “ancient astronauts” in his 1968 book Chariots of the Gods?. He suggested that extraterrestrial beings influenced Earth’s ancient civilizations. He interpreted Sumerian texts and the Old Testament as evidence of these ancient astronauts.

Zecharia Sitchin’s Claims

Zecharia Sitchin’s 1976 book The Twelfth Planet claimed that the Anunnaki were extraterrestrial beings from the planet Nibiru. According to Sitchin, they came to Earth 500,000 years ago to mine gold. He believed they created humans as a slave species through genetic engineering. Sitchin’s ideas are widely dismissed by mainstream historians as pseudoarchaeology.

David Icke’s Reptilian Conspiracy

David Icke expanded on Sitchin’s ideas, proposing that the Anunnaki are reptilian overlords in his reptilian conspiracy theory. Icke’s theory incorporates dragons, Dracula, and Aryan master race ideas.

Conclusion

The Anunnaki, part of the ancient Mesopotamian pantheon, remain a subject of intrigue. Their roles shifted over time from heavenly deities to Underworld judges. While no evidence exists for their collective worship, each Anunnaki deity had a distinct cult and influence over specific cities.

Whether viewed through historical texts or modern conspiracy theories, the Anunnaki continue to captivate imaginations. Their enduring legacy reflects humanity’s fascination with the mysteries of ancient civilizations.

Sources: