Overview of Han Yangling Mausoleum

The Yangling Mausoleum of Han, located at the eastern end of the Xianyang Plain, serves as a joint burial site. It houses the tombs of Jingdi Liu Qi, the fourth emperor of the Western Han Dynasty, and his empress, Wang Zhi. This significant archaeological site spans approximately 6 kilometers in length and varies from 1 to 2 kilometers in width.

Get your dose of History via Email

Historical Significance of Yangling

Yangling serves as the final resting place for Emperor Jing of the Han Dynasty, also known as Liu Qi, and his queen, Wang. Emperor Jing passed away in 141 BC in Chang’an, the then capital of the Western Han Dynasty. Subsequently, he found his resting place in Yangling. Fifteen years later, in 126 BC, Queen Wang also passed away. They now rest together in separate caves within the Yangling mausoleum.

Structural Composition of the Mausoleum

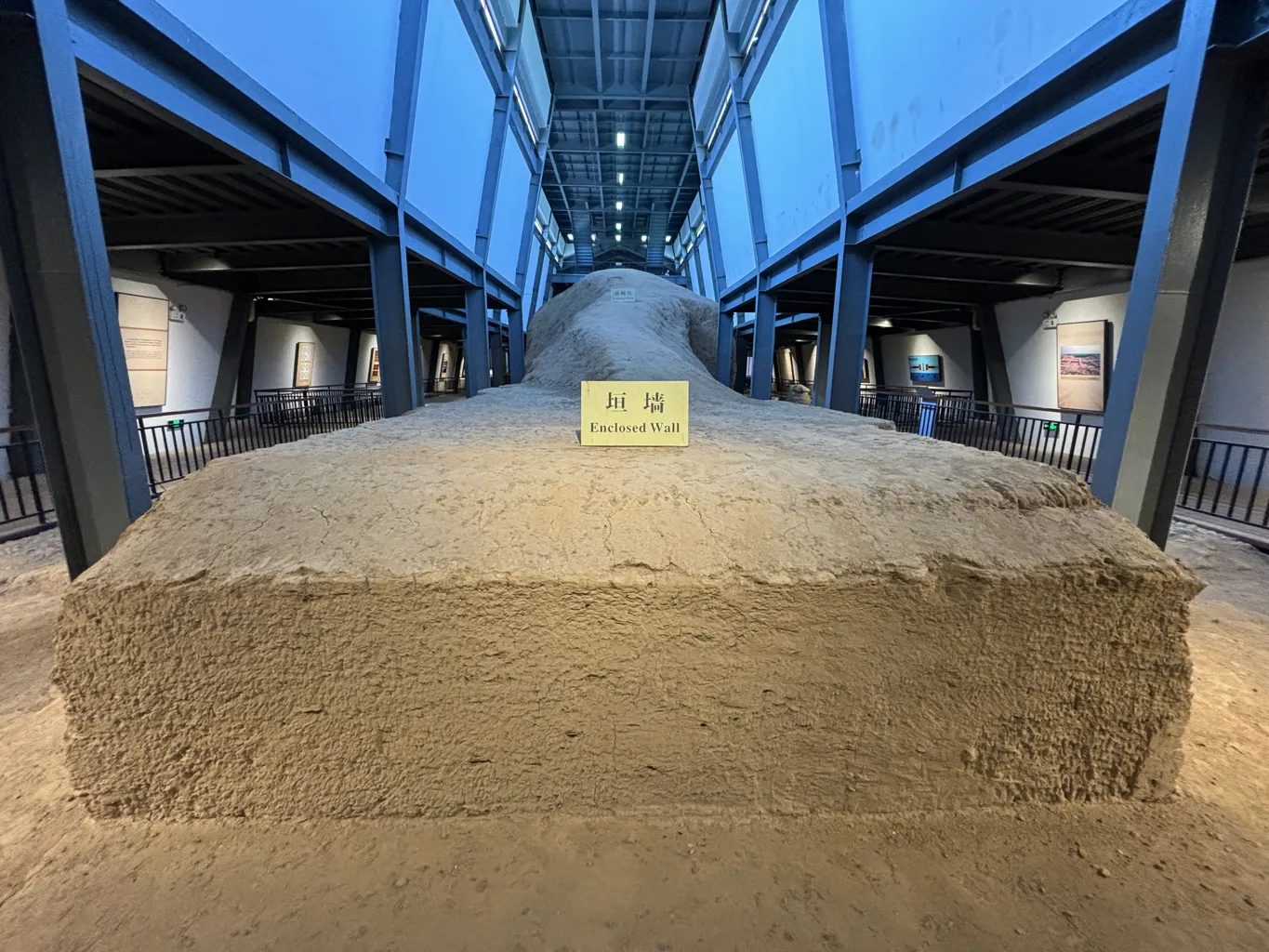

The mausoleum complex comprises three primary sections: the Yangling Cemetery, the Attendant Burial Pits, and Yangling Town. The Yangling Cemetery, known for its meticulous structure and organized layout, forms the core of the site. It features a prominent burial mound and is secured by four guarding corners. Central to the cemetery lies Emperor Jingdi’s Graveyard, encircled by Empress Wang Zhi’s Graveyard, the southern and northern outer burial pits, and the Deyang Temple Site.

Distribution of Attendant Tombs

The attendant tombs predominantly occupy the northern and southern flanks along the East Simamen Route. They are methodically arranged in east-west rows and north-south lines. Researchers have discovered over 130 attendant tombs to date.

Han Yangling: A Window into the Western Han Dynasty

The Han Yangling Mausoleum Complex stands as one of the best-preserved sites from the Western Han Dynasty. It showcases the burial practices and the culture of national ritual sacrifices of the era. This site serves as a crucial resource for studying the material culture, political systems, and spiritual life of the Han Dynasty. Through artifacts like imposing gate-towers, mysterious temple remains, and elegant pottery figures, we gain a vivid glimpse into the period historians later dubbed the Great Reign of Wen and Jing.

Historical Context and Administrative Roles

The “Book of Han·Biao of Officials and Officials,” annotated by Yan Shigu, sheds light on the administrative structure of the time. It details the responsibilities of various officials, including the Taiguan, who oversaw meals, and the Daoguan, who selected and processed ingredients. These roles highlight the sophisticated bureaucratic system that supported the imperial court’s daily functions.

This exploration of Han Dynasty tombs not only reveals the architectural ingenuity of the time but also offers a deeper understanding of the social and political hierarchies that governed ancient Chinese life.

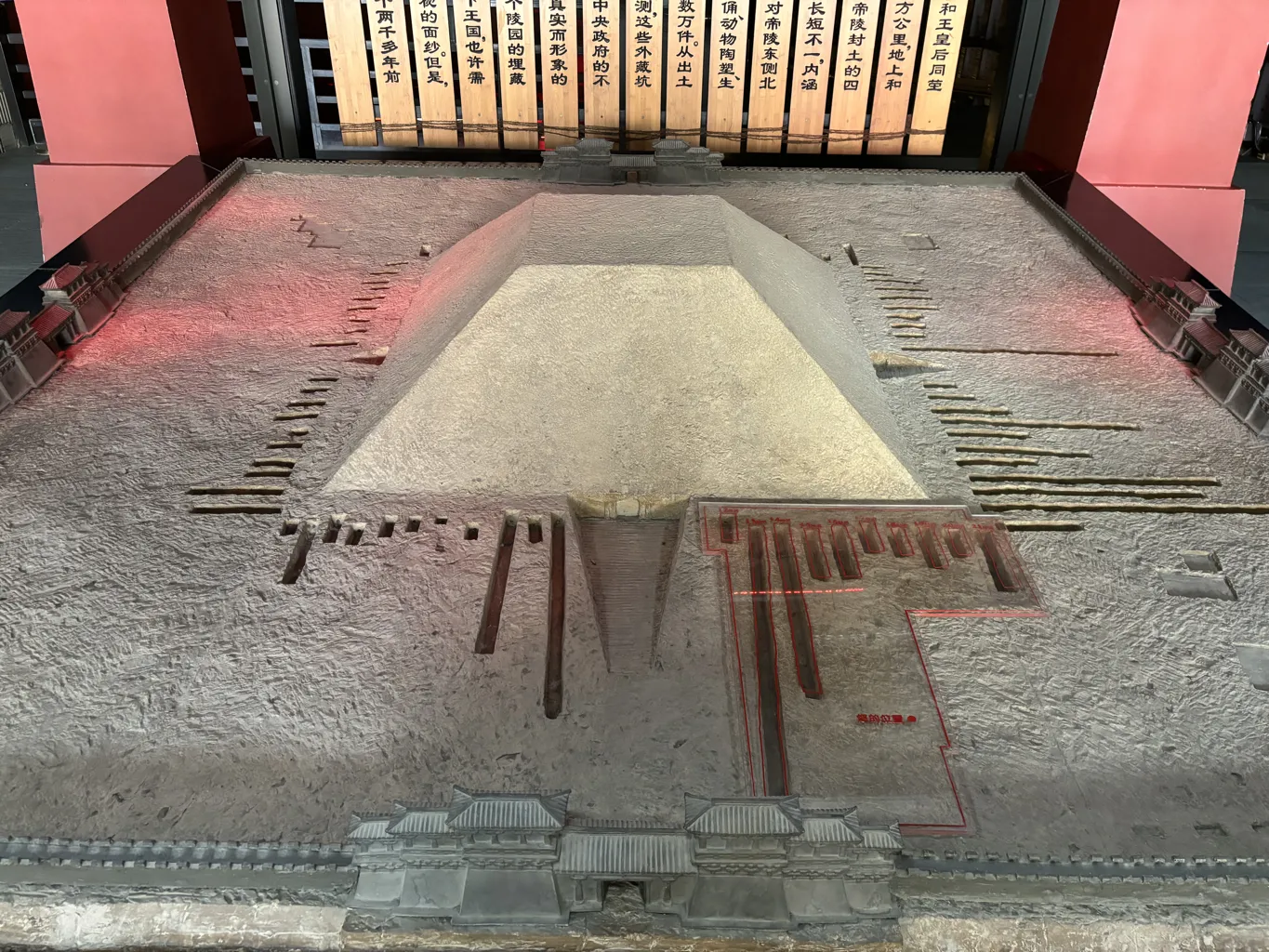

Overview of the Imperial Mausoleum Structure

The imperial mausoleum features a square layout, each side measuring approximately 418 meters. At the center, a tall, bucket-shaped enclosure dominates the space. This central area is encircled by mausoleum walls, each equipped with a centrally positioned door. Beneath these structures lies the tomb chamber. It connects to a tomb passage on each side, with the eastern passage serving as the main route. Notably, 86 external storage pits are scattered between the seals and the walls. Additionally, a drainage canal is present at each corner, enhancing the site’s functionality.

Emperor Jingdi: Architect of Prosperity

In 157 BC, Liu Qi, known posthumously as Emperor Jingdi, ascended as the fourth emperor of the Han Dynasty at the age of 31. He built on his father’s foundations, focusing on strengthening the empire’s political, economic, and military frameworks. His reign, along with his father’s, marked the start of what is known as the Great Reign of Wen and Jing—a golden era characterized by economic prosperity, political clarity, and social harmony.

Emperor Jingdi’s effective governance promoted agricultural advancement and virtuous leadership. He passed away in 141 BC at the age of 41 and was laid to rest in Yangling Mausoleum. His policies and leadership left a lasting impact, positioning the empire for continued success and leaving behind the rich cultural legacy of the Han Yangling for future generations to cherish.

Han Dynasty’s Perspective on Death and Construction

The Han Dynasty held a profound belief that death was as significant as life. Consequently, the construction of imperial mausoleums was a major national event. It was on par with establishing a prince, worshiping at ancestral temples, and mobilizing troops. This construction demanded massive investment, extensive time, and considerable labor, marking it as a significant “national key project.”

Construction Timeline of Yangling

Emperors during the Han Dynasty typically initiated the construction of their mausoleums, known as “Shouling,” upon their accession. Specifically, the main construction of Yangling commenced in the fifth year of Emperor Jing’s reign, 152 BC, and concluded in the fourth year of Yuanshuo, 125 BC, under Emperor Wu. This process spanned twenty-eight years, reflecting a meticulous approach to planning and execution. Nearly three decades of archaeological efforts have since confirmed Yangling’s sophisticated development.

Yangling Town: A Bridge Between Realms

Yangling Town, historically known as Lingyi or Lingxian, served as a crucial administrative area for mausoleums during the early to middle Western Han Dynasty. This area saw an influx of noble families, wealthy merchants, and high-ranking officials relocating near the imperial mausoleum in Chang’an. Situated on the north bank of the Wei River, the region around Xianyang was dubbed “Wulingyuan.” This name stemmed from the proximity of several imperial mausoleums, including those of Emperors Gaozu, Hui, Wu, and Zhao. These mausoleums collectively played a strategic role in safeguarding the capital. Alongside Chang’an, they formed the cultural heart of Guanzhong. This area was renowned for its concentration of elite figures, described poetically as a place where “the crown is like clouds, with seven phases and five public figures.” Yangling’s strategic and cultural significance was paramount in the political and social spheres during the late Western Han Dynasty.

Establishment of the Mausoleum Town

The mausoleum transformed into a town, attracting residents to settle there. The Yanglingyi site, situated in the Jingwei Delta, marks the eastern boundary of this area. It spans approximately 4,300 meters in length and 1,000 meters in width, covering an area of about 4.5 square kilometers. The layout includes 11 east-west roads and 31 north-south roads, creating several well-organized regional units. A main street defines the site’s boundary. To the north, larger buildings likely served governmental functions, while the south housed smaller residential structures. Additionally, archaeologists discovered a city wall and a moat on the southern perimeter. The site’s orderly design, along with the abundance of building materials and inscribed tiles and sealing mud, sheds light on the Han Dynasty’s social production, cultural life, and urban planning.

Han Dynasty Royal Mausoleums: A Microcosm of Empire

The Han Dynasty’s approach to constructing royal mausoleums mirrored their views on life and death. They believed in the immortal spirit and maintained burial traditions that honored the dead as if they were still living. Thus, the mausoleums replicated real society, serving as a miniature version of the Han Empire. Since the 1970s, archaeological advancements have peeled back the layers of mystery surrounding these sites. The Han Yangling Mausoleum Complex, in particular, has revealed a scaled-down empire, marked by its rational structure and rich contents. Archaeologists have unearthed over a hundred thousand relics, varying in type, shape, and craftsmanship. These artifacts are crucial for studying the Han Dynasty’s political systems, material culture, and ideological concepts.

The Han Yangling Mausoleum Complex: Symbolism and Structure

The Han Yangling Mausoleum Complex served as the final resting place for Emperor Jing and Queen Wang, who were buried in separate but adjacent tombs. This complex includes the emperor’s mausoleum, sleeping gardens, external storage pits, and other ancillary facilities, all centered around the emperor’s tomb. Researchers suggest that the layout of Yangling was influenced by the urban design of Chang’an, the Han capital. The cemetery’s design, with its organized structure and clear organization, symbolically mirrors Chang’an. The emperor’s mausoleum, the dormitory, and the cemetery walls could represent the palaces, official offices, ritual buildings, and city walls, respectively.

The cemetery spans a rectangular area, measuring 1820 meters in length and 1380 meters in width, oriented from east to west. The imperial mausoleum is strategically placed in the western central part, with other elements like rear mausoleums and ritual sites distributed throughout. This layout not only emphasizes the importance of the imperial mausoleum but also reflects a highly centralized hierarchical concept inherent to the Han Dynasty.

Central Government Structure in the Western Han Dynasty

The Western Han Dynasty’s central government structure was known as “San Gong Jiu Qing.” This framework was crucial for governance. Over time, many seals and clays representing these offices have surfaced at Han Yangling. “San Gong” included positions similar to today’s premier and vice-premiers. These were Cheng Xiang, Tai Wei, and Yu Shi Dai Fu.

“Jiu Qing,” subordinate to “San Gong,” encompassed various high-ranking offices. These included Taichang, Guang Luxun, Weiwei, Taipu, Tingwei, Da Honglu, Zongzheng, Dasinong, and Shao Fu. Each office corresponded to different ministerial roles within the central government. Other unearthed seals, such as “Yangling Ling Yin,” “Taiguan Zhi Yin,” “Yongxiang Cheng Yin,” “Dongzhi Ling Yin,” and “Ganquan Cang Yin,” further illustrate the administrative complexity of the time.

Role of Prisoners in Mausoleum Construction

Prisoners, often sentenced to hard labor for their crimes, played a crucial role in these monumental construction projects. Unfortunately, they frequently succumbed to injuries and illnesses due to strenuous physical work and poor living conditions, leading to their burial at the construction sites.

In the case of Yangling, a significant discovery was made northwest of the mausoleum. An 80,000 square meter cemetery was unearthed, containing the remains of tens of thousands of individuals. The graves were haphazardly arranged without coffins, and the burial styles varied widely. The disordered bones and the presence of torture implements, such as tongs and shackles, suggest that these were the remains of prisoners who labored on the mausoleum. This discovery highlights the harsh realities faced by these laborers and provides insight into the labor practices of the time.

Western Han Dynasty Sacrificial System

The Western Han Dynasty developed a comprehensive sacrificial system for imperial mausoleums. This system included ceremonial buildings such as mausoleums, temples, dormitories, and banquet halls. Additionally, institutions and managers dedicated to worship services at these imperial sites were established. The mausoleum temple, constructed adjacent to the emperor’s mausoleum, served as a site for descendants to honor their ancestors. The sleeping hall, equipped with the emperor’s attire, staffs, and elephant tools, functioned as the space where the emperor’s spirit could dine and reside. Literature from the period details that sacrifices occurred daily in various locations within the temple grounds, including the sleeping and toilet halls, with specific offerings scheduled for certain days.

Funeral Rites and Sacrifices in the Western Han Dynasty

The Western Han Dynasty adhered to a funeral system that emphasized treating death as if it were life. This philosophy extended to the elaborate sacrifices made in imperial tombs. These rituals included annual, seasonal, monthly, and daily sacrifices. The “Suiji” was a significant annual event, showcasing the dynasty’s reverence for the afterlife and its meticulous attention to ritualistic detail.

Funeral Rituals in the Western Han Dynasty

The Western Han Dynasty embraced a funeral system that meticulously imitated real life. The Emperor himself hosted the Annual Sacrifice, a grand and highly ritualized event. Senior officials, appointed by the Emperor, conducted the Seasonal Sacrifice. Junior officials took charge of the Monthly Sacrifice, while temple staff from the mausoleum managed the Daily Sacrifice. Archaeologists discovered several sacrificial constructions at the Han Yangling Mausoleum. These findings, with their regular distributions and large scopes, vividly illustrate the elaborate sacrificial practices of the era.

The Satellite Tombs of the Western Han Dynasty

The Western Han Dynasty’s imperial mausoleums included a unique burial area. This area was designated for the emperor’s relatives and distinguished ministers. It allowed them to rest near the emperor. This practice showcased the emperor’s immense kindness. The size and location of these burial sites mirrored the political status and personal closeness to the emperor.

Location and Structure of the Satellite Tombs

The tombs in the North District are situated outside the north gate of Yangling Cemetery. Meanwhile, the East District tombs lie outside Yangling Cemetery, flanking the north and south sides of East Simamen Road. These tombs form a crucial part of the mausoleum area.

In the North District, there are only two independent tombs. Both tombs are shaped like the character “middle.” They feature external storage pits around them. Due to their proximity to the emperor’s mausoleum, they are believed to be the resting places of Emperor Jing’s concubines.

Daily Appliances of the Western Han Dynasty

In the Western Han Dynasty, people classified daily appliances by material quality into categories such as gold, silver, copper, iron, pottery, jade, bone, horn, and lacquer. These items served practical purposes and typically had fixed shapes. They included containers for water, washstands, stoups, cookers, and tableware. Emperors Wendi and Jingdi promoted frugality in burials. Emperor Wendi decreed the use of pottery instead of metal, a practice his successor, Emperor Jingdi, continued. This shift is evident in the predominance of pottery over metal objects in the Han Yangling Mausoleum.

Han Dynasty Pottery: A Reflection of Cultural Prosperity

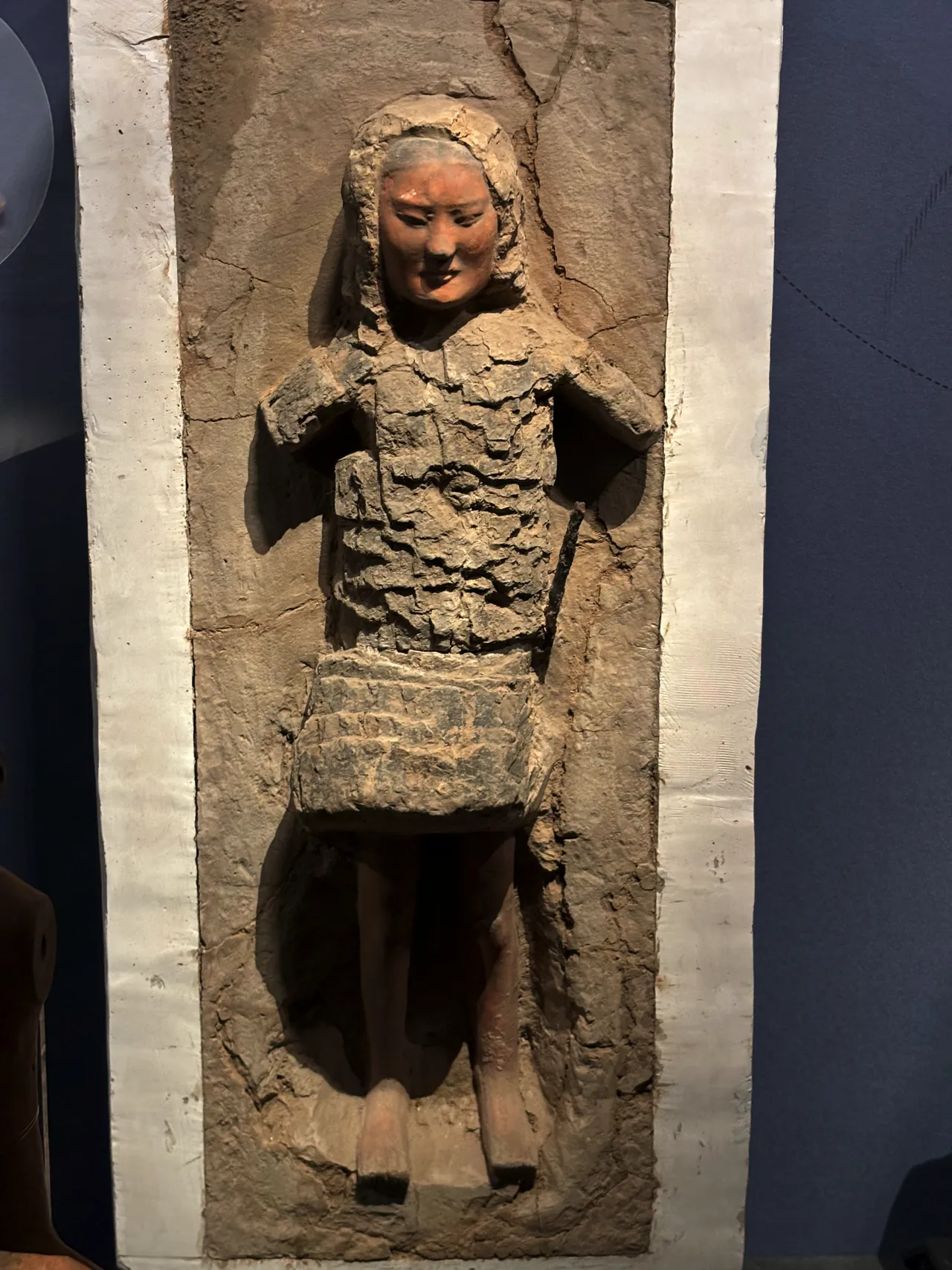

During the early Han Dynasty, the social economy began to flourish, and cultural integration sparked new aesthetic desires. Royal craftsmen, building on the Qin culture’s garment-shaped pottery figurines, incorporated elements from the Chu region. They crafted royal-clothed pottery figurines with complex techniques and a stunning appearance. These figurines were lifelike, delicately carved, and well-proportioned. They featured round facial features and rich expressions, each representing different identities. Behind each figurine, a touching story seemed to lurk, collectively painting a vivid social tableau that narrated the history of the Han Empire with style.

Pottery Figurines in the Western Han Dynasty

Pottery figurines from this period came in two main types: dressed and clay-coated, with the former being more common. The standard procedure for creating these figurines involved several detailed steps. Artisans patterned the limbs and trunk first. They then attached the nose, ears, and other appendages, followed by intricate facial carvings. The figurines underwent an initial kilning, received their colors, and then entered a second kilning. Each figurine had two holes on the shoulders for arm attachment. The final step involved dressing the figures in various styles, reflecting the identity of each figure. This meticulous process highlights the craftsmanship and cultural significance of pottery figurines in the Western Han Dynasty.

Pottery Animals of Han Yangling Mausoleum

Archaeologists have discovered numerous pottery animals in the satellite pits of the Han Yangling Mausoleum. These include domestic animals such as horses, oxen, pigs, goats, dogs, and chickens. These animals served as food sources for the individuals buried in the tombs. This discovery highlights the opulent royal lifestyle and advanced animal husbandry of the Western Han Dynasty. Artists of that era crafted these pottery animals in a realistic style. They depicted horses as strong, agile, and brave; oxen as honest and straightforward; pigs as clumsy and humorous; goats as timid and docile; and dogs as keen and alert. The detailed and vivid sculptures showcase the ancient artists’ keen observation of daily life and their exceptional talent in statuary.

Vehicle System in the Western Han Dynasty

The Western Han Dynasty featured a diverse array of vehicles, reflecting the social hierarchy of the time. Historical records indicate that vehicles designated for royal family members were more sophisticated and comfortable compared to those used by junior officials. Excavations at the Han Yangling Mausoleum have unearthed many remains of these vehicles, predominantly the Yaoche. This lightweight vehicle typically featured a single slanting thill, two large wooden wheels, a long carriage, and an elliptical umbrella-like canopy on top, with a rear door. These vehicles were likely standard for central government officials during that period. The exhibits of reproduced wooden vehicles from the Western Han Dynasty provide further insight into this aspect of feudal society.

Archaeological Insights into the Yangling Mausoleum

Archaeologists have unearthed a significant number of imperial and high-level tombs in the Yangling Mausoleum area. These tombs often include external storage pits. Current data suggests three levels of these pits: one directly outside the tomb under the seal, another outside the seal but within the mausoleum walls, and a third outside the mausoleum boundaries. The arrangement and number of these pits reflect the hierarchical nature of ancient Chinese society and its close ties to imperial power.

Nanquemen Site Details

Spanning 134 meters in length from east to west, the Nanquemen site varies in width from 10.4 to 27.2 meters. It stands 6 meters tall, covering an area of about 2,380 square meters. The site preserves remnants of terraces, cloisters, water basins, steps, and column grooves. Both the eastern and western sections mirror each other in scale and structure, showcasing the symmetrical design typical of ancient Chinese architecture.

Architectural Symmetry and Color Symbolism at the East Gate

The East Gate of the imperial mausoleum mirrors the Nanquemen site in scale, shape, and structure. It lies adjacent to the main tomb passage to the west and the East Shinto to the east. Archaeological findings indicate that the East Gate predominantly features cyan decorations, while the South Gate displays red hues. These color choices reflect the “Five Elements” theory, a significant cultural element during the Western Han Dynasty.

Ancestral Temple Ruins

Located southeast of the imperial mausoleum, the ancestral temple ruins feature a nearly square layout, each side measuring approximately 260 meters. The structure comprises walls, gates, curved side rooms, and central buildings, collectively forming an “Hui”-shaped configuration. The central pillar foundation stone, with a diameter of 1.4 meters, is surrounded by numerous building materials and sacrificial artifacts. Scholars commonly believe this significant archaeological site, situated on elevated terrain, to be Deyang Palace, the mausoleum of Emperor Jing of the Han Dynasty. This site is recognized as the earliest mausoleum discovered in archaeological studies and has significantly influenced the architectural style of ritual buildings in subsequent periods.

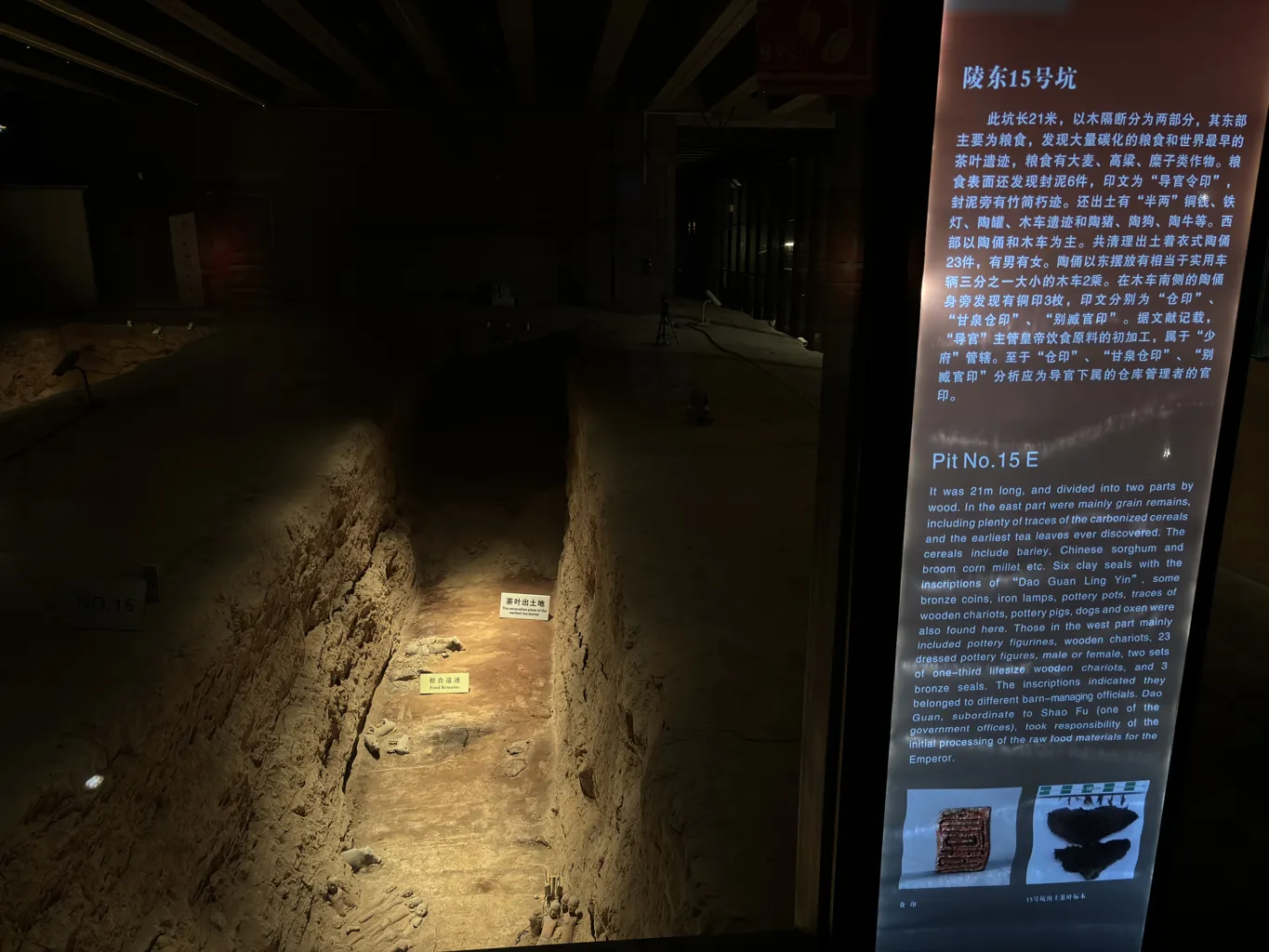

Discoveries at Waizang Pit No. 15

On the east side of the imperial mausoleum, Waizang Pit No. 15 offered remarkable finds. Archaeologists discovered seals labeled “Cang Seal” and “Ganquan Cang,” among others. These artifacts, along with remains of millet, wheat, and the world’s earliest tea specimens, provide a glimpse into the dietary practices of the era. The Daoguan, one of three major agencies under the Shaofu responsible for imperial cuisine, played a crucial role in food preparation, as evidenced by the unearthed items.

Discovery of Warrior Figurines at Waizang Pit

Archaeologists recently excavated a significant number of warrior figurines at the Waizang Pit, located in the Southern District. These figurines, impressively adorned, featured bidn (a traditional black gauze crown hat), forehead ties, battle robes, and belts. Additionally, they were coated with armor and had their legs bound up to the knees with teng. Each figurine was equipped with iron swords, wooden shields, crossbows, and other weaponry. Interestingly, some figurines also bore miniature seals and copper coins, while others showcased decorations of small shells. The predominant color of the clothing on these figurines was red, aligning with the “Shang Chi” concept documented during the Han Dynasty.

Han Dynasty Seal System

The Han Dynasty employed a distinctive system for official seals. According to the “Book of Han·Biao of Hundred Officials and Ministers,” officials holding a rank of 2,000 shi and above used silver seals adorned with green ribbons. Meanwhile, those with a rank of 600 shi or higher utilized bronze seals with black ribbons. Yan Shigu, in his annotations on “Han Jiuyi,” noted that the silver seals featured turtle buttons. He further mentioned that officials ranked from 600 to 300 shi used bronze seals with nose buttons.

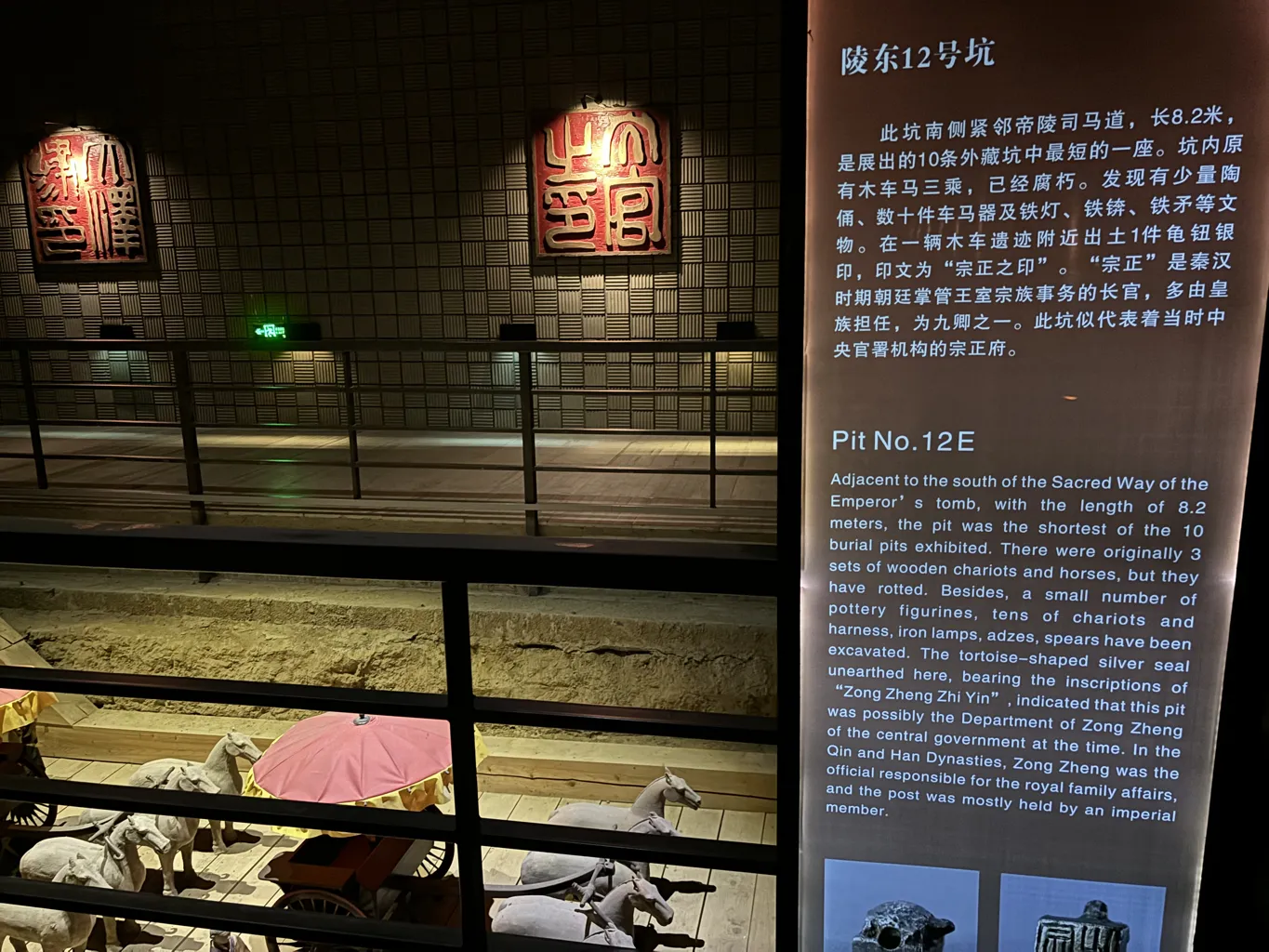

Archaeological Discoveries Related to Han Seals

Excavations on the east side of the imperial mausoleum unearthed significant artifacts. In No. 12 Waizang Pit, archaeologists found a turtle-button silver seal known as the “Zongzheng seal.” This seal aligns with the descriptions of Zongzheng official seals from Han Dynasty records. The Zongzheng, ranking among the nine ministers, typically comprised esteemed members of the royal family. They managed royal family affairs and held significant influence. Additionally, in the same pit, a bronze “Ozejin seal” with a nose button was discovered. Unlike the Zongzheng seal, the Ozejin seal lacks documentation in historical texts. Given its location and design, it likely belonged to a Zongzheng official.

Unearthed Measuring Instruments

In the same excavation at the Waizang Pit, archaeologists found complete sets of ancient measuring instruments. These included various copper weights and tielei, essential for measuring length, volume, and weight in ancient times. Although these instruments now serve a symbolic purpose, they were practical tools in their era. The set comprised five copper measuring utensils, each representing a different volume unit from the Han Dynasty—yue, he, sheng, dou, and dendrobium. Additionally, some vessels featured a cross-shaped beam known as “gai,” utilized to level grain and ensure its fair distribution. This discovery provides invaluable insight into the standardization and precision of ancient measurement practices.

Archaeological Discoveries and Insights in Eastern Area

After extensive archaeological exploration in the eastern area, researchers uncovered a vast burial site. It spans approximately 3.5 square kilometers. Centered around the East Simamen Road axis, this site revealed a large-scale, numerous, and orderly cemetery. The burial period in these tombs ranges from the time of Emperor Jing of the Western Han Dynasty to the middle of the Eastern Han Dynasty. This spans about 200 years, offering a deep insight into the era’s burial practices and social hierarchies.

Restoration of Tomb No. 9’s External Storage Pit

The external storage pit No. 1 of Tomb No. 9 in the East District, known as M9K1, offers a fascinating glimpse into ancient practices. Archaeologists unearthed a significant collection of painted pottery and ceramic animals from this site. The pottery features a fine texture, unique shapes, and brilliant colors. Interestingly, these vessels once held meat, grain, or wine, indicating their use in storage. The ceramic figures, including cows, horses, sheep, pigs, dogs, and chickens, were arranged meticulously. These lifelike figures highlight the advanced state of animal husbandry during the Jing Emperor’s reign. They also reflect the social and economic stability and prosperity under the governance of Wen and Jing.

Overview of Pit No. 12 E

Located just south of the Sacred Way of the Emperor’s tomb, Pit No. 12 E measures 8.2 meters in length. It stands as the shortest among the 10 burial pits on display. Initially, this pit housed three sets of wooden chariots and horses, which have since decayed. Archaeologists also unearthed a modest collection of pottery figurines, numerous chariots, harnesses, iron lamps, adzes, and spears. A notable discovery was a tortoise-shaped silver seal with the inscription “Zong Zheng Zhi Yin.” This suggests that Pit No. 12 E might have served the Department of Zong Zheng, a central government body during the Qin and Han Dynasties. Typically, a royal family member held the position of Zong Zheng, who managed royal family affairs.

Examination of Pit No. 13 E

Spanning 94 meters in length, 3 meters in width, and depths ranging from 2.4 to 2.8 meters, Pit No. 13 E is the longest of the displayed burial pits. It divides into two distinct sections. In the eastern section, archaeologists found a variety of pottery animals including piglets, pigs, sheep, goats, and both domestic and wild dogs. The animals face north and west, aligning with the chamber’s direction. The pit contained a staggering total of 1391 pottery animals, organized in two layers. This array included 235 painted pottery goats, 189 pottery sheep, 458 pottery dogs, 455 pottery pigs, and 54 pottery piglets, creating a veritable tableau of domestic life.

The western section primarily featured a life-size wooden chariot and a vast assortment of pottery. Although the wooden chariot has decayed, leaving only organic remains and bronze parts, the pottery collection remains extensive. It includes 55 barns, 33 pots, and 12 cocoon-shaped pots. Additionally, crops like broom corn millet and Chinese sorghum were found alongside some animal remains. A clay seal inscribed with “Tai Guan Cheng Yin” was also unearthed, hinting that this pit might have functioned as the imperial palace’s food storage. The title Tai Guan refers to the official in charge of the Emperor’s dietary needs, suggesting that the pit symbolized the royal underground storage sealed by Tai Guan.

Discoveries in Pit No. 14 E

Archaeologists uncovered a wooden chariot and various pottery animals, including chickens, dogs, and pigs in Pit No. 14 E. Additionally, they found pottery bowls, cocoon-shaped pots, stone mills, and lacquer wares. Remarkably, atop the lacquer wares lay over 30 clay-seal boxes. Interestingly, only one box contained a clay seal, inscribed with “Tai Guan Ling Yin.” Nearby, a bronze seal bearing a name was also discovered. In the eastern section of the pit, researchers found two sets of oxen skeletons and some smaller animal bones. The inscriptions suggested that this pit had a similar function to Pit No. 13 E.

Findings in Pit No. 15 E

Pit No. 15 E, measuring 21 meters in length, was divided into two sections by a wooden barrier. The eastern part housed mainly grain remains, including traces of carbonized cereals and the earliest discovered tea leaves. The cereals identified were barley, Chinese sorghum, and broom corn millet. Six clay seals bearing the inscriptions “Dao Guan Ling Yin” were found here, along with some bronze coins, iron lamps, pottery pots, and traces of wooden chariots. Pottery representations of pigs, dogs, and oxen were also present. The western section contained pottery figurines, wooden chariots, and 23 dressed pottery figures, both male and female. Two sets of one-third life-size wooden chariots and bronze seals were also unearthed. The inscriptions indicated that these items were associated with different barn-managing officials. Dao Guan, a subordinate to Shao Fu (a government office), was responsible for the initial processing of raw food materials for the Emperor.

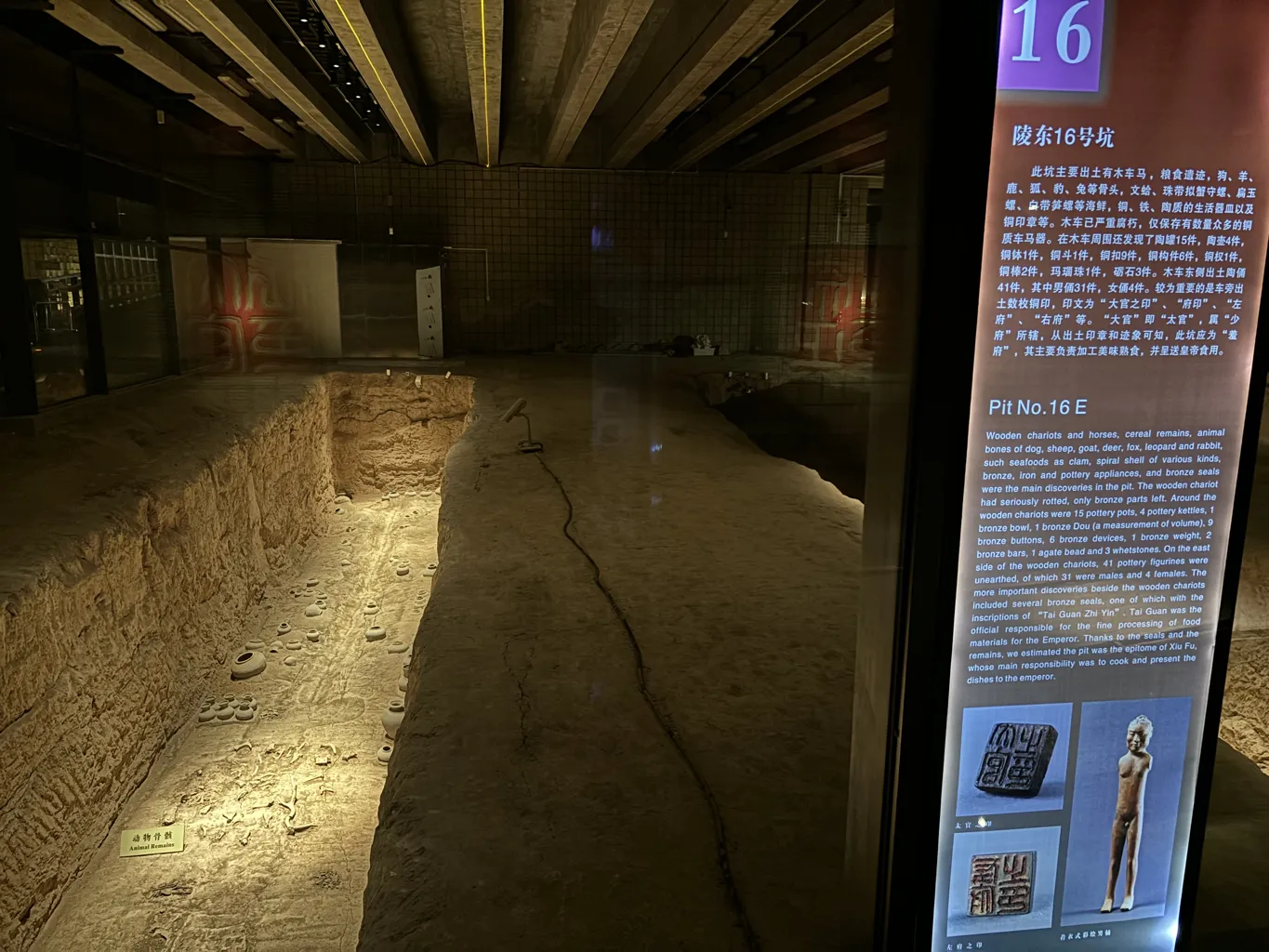

Discoveries in Pit No. 16 E

Archaeologists unearthed a variety of artifacts in Pit No. 16 E. They found wooden chariots and horses, although the wood had severely rotted, leaving only the bronze components. Surrounding the chariots, they discovered 15 pottery pots, 4 pottery kettles, and a range of bronze items including a bowl, a Dou (a volume measure), buttons, devices, a weight, two bars, and an agate bead. Additionally, they found 3 whetstones. On the east side of the chariots, 41 pottery figurines came to light, with 31 male and 4 female figures. Notably, several bronze seals were also found, one bearing the inscription “Tai Guan Zhi Yin.” Tai Guan managed the fine processing of food for the Emperor. These findings suggest that Pit No. 16 E might have been a representation of Xiu Fu’s role, who was tasked with cooking and presenting dishes to the emperor.

Findings in Pit No. 17 E

Pit No. 17 E measured 9.4 meters in length, 2.8 meters in width, and 2.3 meters in depth. It featured a sloped passage at the western end and was divided into three sections. The western section housed wooden chariots and horses, each drawn by two horses with a single shaft, all facing west. The central section contained 10 dressed pottery figurines, including 7 males and 3 eunuchs. The eastern section held daily appliances. Among the artifacts found were three sets of wooden chariots and horses, bronze coins, small bronze weights, pottery pots, pottery basins, iron agricultural tools, and two bronze seals. One seal was inscribed with “Chang Le Gong Che,” and the other with “Huan Zhe Cheng Yin.” Huan Zhe Cheng, associated with Shao Fu, was responsible for overseeing the eunuchs in the royal palace. The meaning of “Chang Le Gong Che” remains unclear.

Excavation Details of Pit No. 18 E

Workers divided Pit No. 18 E into three sections. At the western end, they positioned two wooden chariots, now rotted, facing west. They found over one hundred pieces of chariots and harnesses. In the northwest robbery hole, archaeologists discovered 7 pottery figures and 2 pottery dogs. To the east, they found 92 dressed pottery figurines. These included 21 males, 23 eunuchs, and 22 painted females, along with 26 fragments of pottery figures. Some figures held bronze seals; in total, they found 4. One particular bronze seal bore the inscriptions “Yong Xiang Cheng Yin.” Historically, Yong Xiang was a location in the imperial palace for detaining palace maids and imperial concubines. Under Emperor Wudi, it was renamed Ye Ting, managed by eunuchs overseeing palace affairs.

Discoveries in Pit No. 19 E

Pit No. 19 E featured two sections, separated by wooden partitions. In the western half, the team unearthed wooden chariots and horses, wooden boxes, and various pottery items. All wooden implements had completely rotted. The pottery collection included 46 figurines, with 11 painted females and 35 males. They also found pottery oxen, chickens, pigs, and dogs, along with iron forks, hooks, shuttles, adzes, whetstones, pottery pots, bowls, cauldrons, and a bronze seal inscribed with “Tu Fu.” In the eastern half, only traces of wooden boxes and cloth remained. The cloth, now black and brown, still showed identifiable weaving lines. In the Western Han Dynasty, “Xing Tu” referred to criminals forced into labor by local authorities. Thus, “Tu Fu” likely represents a governmental office supervising these criminals.

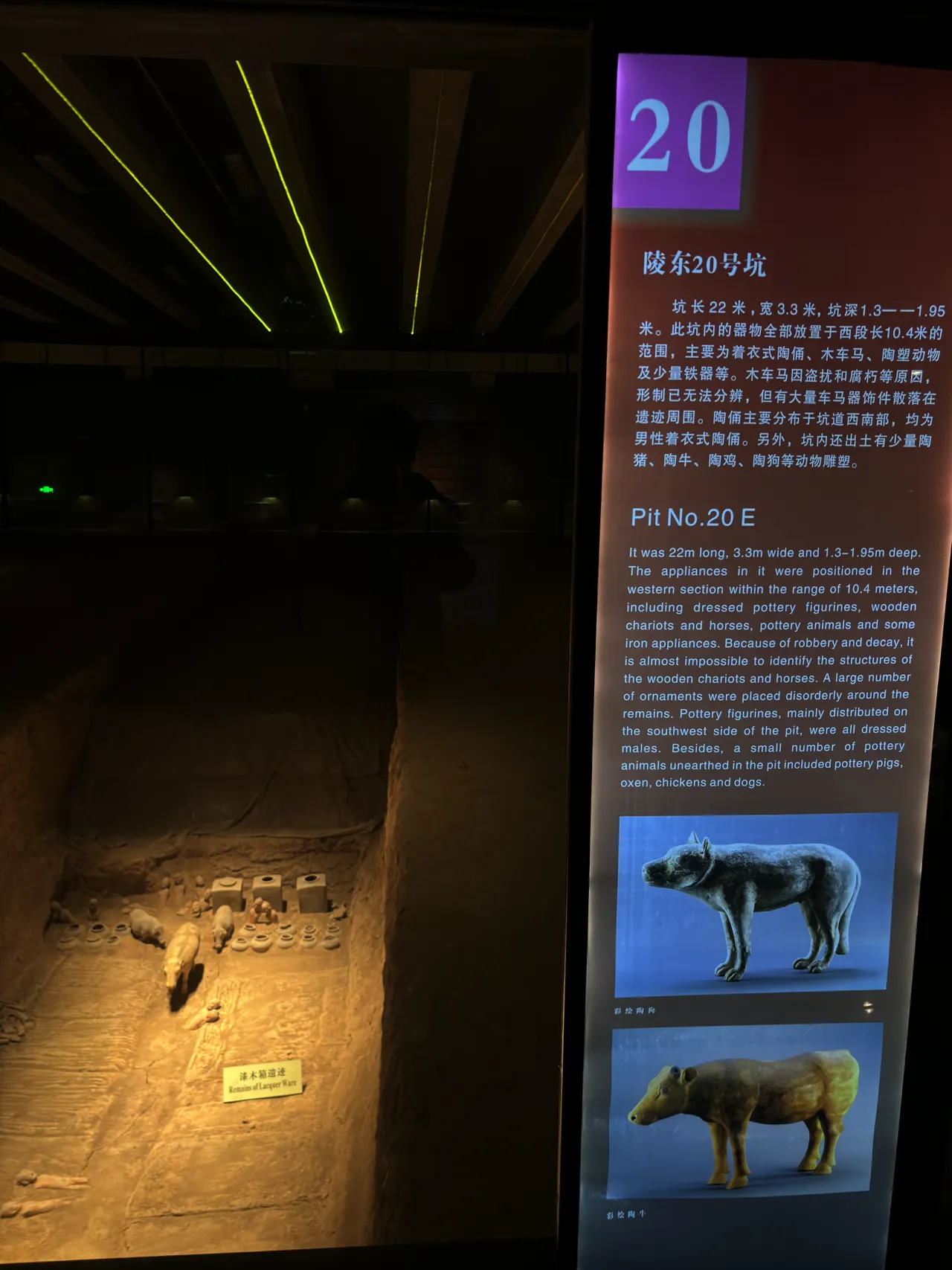

Analysis of Pit No. 20 E

Pit No. 20 E measures 22 meters in length, 3.3 meters in width, and varies in depth from 1.3 to 1.95 meters. Archaeologists found the artifacts mainly in the western section, spanning approximately 10.4 meters. The contents included dressed pottery figurines, wooden chariots, horses, and various pottery animals, alongside some iron appliances. Unfortunately, due to theft and decay, identifying the wooden structures has become nearly impossible. A large array of ornaments lay scattered around these remains. Notably, the pottery figurines, all representing dressed males, clustered on the southwest side of the pit. Additionally, the pit housed a small collection of pottery animals, such as pigs, oxen, chickens, and dogs.

Examination of Pit No. 21 E

Pit No. 21 E extends 20.1 meters in length, 2.9 meters in width, and reaches a depth of 2.6 meters, with an overall depth from the current ground level of 6.4 meters. Similar to Pit No. 20 E, this pit also contained wooden chariots and horses on its western side, though these have suffered significant rotting. Positioned near these wooden artifacts were an iron sword and a seal inscribed with “Dong Zhi Ling Yin.” Dong Zhi, a junior official, was responsible for overseeing weaving and dyeing operations. The pit revealed 84 dressed pottery figurines, including 49 males, 6 eunuchs, and 29 painted females. Additionally, traces of wooden boxes, pottery, iron appliances, and pottery representations of dogs, chickens, and oxen were found distributed across the western and eastern halves of the pit.

Overview of Empress Wang Zhi’s Graveyard

Empress Wang Zhi’s graveyard is located in Xingping, Shaanxi. It lies northeast of Emperor Lingdi’s graveyard. The site features a square layout, each side measuring approximately 350 meters. A 20-meter-wide rammed earth wall encloses the area.

Structural Details of the Graveyard

At the center of the graveyard, a prominent grave mound rises. It measures about 160 meters at the base and 55 meters across the top, with a height of 25 meters. Surrounding the central mound, 28 outer burial chambers radiate outward. Each chamber connects to the mound via one of four tomb passages. The eastern passage serves as the main route.

Architectural Comparison and Historical Marker

The design of Empress Wang Zhi’s graveyard mirrors that of the Emperor’s, albeit on a slightly smaller scale. Interestingly, a stone tablet stands to the south of the grave mound. It bears the inscription “Mausoleum of Her Emperor Hudy.” This marker was erroneously placed during the Qing Dynasty.

Layout and Design of Emperor Sinsdis’ Graveyard

Emperor Sinsdis’ graveyard, oriented from west to east, adopts a square plan. Each side measures approximately 100 meters, reflecting the architectural norms of the Han Dynasty. The graveyard is fortified by a 3-meter-wide rammed earth wall. Notably, each of the four walls features a three-terraced gate, central to its structure.

Central Tomb Structure

At the heart of the cemetery lies a large platform mound. This mound measures 100 meters at the base and 60 meters at the top, with a height of 34 meters. Beneath this mound, the Emperor’s chamber is strategically placed. This W-shaped chamber connects to tomb passages extending in all four cardinal directions. The main tomb passage, located on the east, is the longest.

Symbolism and Layout of Outer Burial Pits

Surrounding the central tomb, 80 outer burial pits are strategically placed. Of these, 81 encircle the tomb, and six are located in the northeast section of the cemetery. This arrangement symbolizes the Emperor’s palace and the administrative departments, mirroring the centralized power of the Western Han Dynasty.

The Towers

The tower, originally known as Guan, evolved from defensive high-terrace constructions. Initially, builders used a single-platform design. Subsequently, they introduced the double-platform tower. They erected these on both sides of the gate or gateway in high-level constructions, leading to the name gate-tower. The concept of the tower originated during the Shang and Zhou Dynasties. It reached its zenith during the Han and Tang Dynasties. However, it began to decline in the Ming and Qing Dynasties. Today, the surviving towers fall into various categories. These include gate-towers, palace-towers, mausoleum-towers, tomb-towers, temple-towers, and residence-towers. Each category reflects its specific nature and function.

The Gatehouses

The Han Dynasty favored constructing gatehouses on both the inner and outer sides of gates. Specifically, the South-Gate Tower in HYMC showcases this design. It features four symmetrically organized gatehouses. These include an inner and an outer house on each side of the gate. This arrangement aligns perfectly with ancient records. These documents mention the presence of four gatehouses near a gate. This design not only highlights the architectural preferences of the period but also underscores the importance of symmetry and structure in Han Dynasty constructions.

Overview of the South Gate-Tower Excavation

The South Gate-Tower at HYMC marks the southern entrance to the emperor’s burial site. In 1997, the Shaanxi Archaeological Research Institute initiated a large-scale excavation of this site. They discovered that the gate consists of two symmetrical towers.

Architectural Significance of the Towers

Each tower’s blueprint reveals a unique tri-platform structure, resembling a sequence of three diminishing rectangles. This design aligns with the top-tier gate tower style from ancient China, as documented in historical texts. This style underscores the architectural sophistication and cultural importance of the era.

Revitalization of the Protection Hall of the South-Gate Tower

In April 2003, builders completed the Protection Hall of the South-Gate Tower (PHSGT), a structure inspired by Han architecture. They opened it to the public, showcasing a commitment to both preserving and utilizing heritage. Today, this restored hall presents a fresh appearance. It plays a crucial role in advancing scientific heritage protection.

The Grandeur of Han Royal Tombs

Since their construction, the Han royal tombs had epitomized prosperity. Dozens of royal mounds, with their gate-towers’ flying eaves reaching towards the sky, dotted the landscape. The sacrifice ceremonies held were grand and luxurious, while mausoleum towns crowded the Xianyang Terrace. Despite later dynasties’ reconstructions, homage ceremonies, and maintenance efforts, disasters such as fires, wars, tomb robberies, and natural erosion inflicted damage. The once bustling scenes, like the crowded streets along the Wei River and the grand buildings on the capital’s central road, eventually faded with time.

Since the founding of the People’s Republic of China, the government has supported the preservation, presentation, and utilization of these historical sites. Modern technologies and scientific archaeology have been employed to protect these sites effectively. Generations of archaeologists and museographers have initiated sample protection and presentation projects. They have developed a system for the effective protection of large sites, ensuring the integrated preservation of historical patterns. These efforts have successfully represented the profound, grand, and simple historical scenes of the Han royal tombs.

Archaeological Endeavors at HYMC

Over time, generations of archaeologists have diligently worked at the Han Yang Mausoleum (HYMC). They have unearthed treasures from the Han Dynasty, restoring their original splendor. Consequently, the prosperity of that era has resurfaced. History serves as a mirror, allowing us to gain new insights by revisiting the past. Emperor Jingdi, for instance, reduced penalties and taxes. He adhered to natural laws, fostering a peaceful and harmonious society. This set a robust foundation for Emperor Wudi’s significant achievements.

Cultural Heritage and National Identity

HYMC stands as the cultural heritage site with the most comprehensive protection and presentation systems. It also boasts rich archaeological findings. This site marks a crucial period in the formation of Han culture and nationality. The national consciousness, political concepts, ideologies, and value systems that developed during this time continue to nourish our national identity. They provide vital energy for national rejuvenation.

Preservation and Innovation at HYMC

HYMC’s achievements in cultural heritage preservation and presentation stem from a deep understanding of Han history and culture. These efforts represent the practical application of creative transformation and innovative development. As cultural heritage and museum

Queee Gran Civilización !!!

Muchas Gracias por presentarse , siguen siendo Genios !!!

Honor y Respeto.

Thanks for this article! Enjoyed reading about the Han period!!