Introduction

The Indonesian archipelago, a vast expanse of islands rich in cultural diversity and history, is home to a remarkable tradition of megalithic monument construction that spans centuries. Among these islands, Nias stands out for its unique megalithic practices, deeply rooted in the island’s indigenous beliefs and social structures. The megaliths of Nias Island, comprising stone statues, tombs, and other ceremonial structures, are not merely architectural feats but are imbued with significant cultural and spiritual meanings.

Get your dose of History via Email

The tradition of erecting megalithic monuments in Indonesia is observed in two distinct periods. The initial phase commenced in the 7th and 8th centuries AD in East Java and gradually spread to other regions, including South and Central Sumatra and Lore Lindu in Central Sulawesi, continuing until the 13th to 15th centuries AD. A resurgence of megalithic construction began in the 16th century and persists to the present day, expanding to include islands such as Sumba, Flores, and notably, Nias, along with North Sumatra and Central Sulawesi. This enduring tradition reflects the indigenous populations’ interactions with external influences, including Hindu-Buddhist kingdoms and European merchants, which contributed to the evolution of megalithic practices.

The megaliths on Nias Island, as in other parts of Indonesia, serve multiple purposes. They are erected in honor of living leaders or to commemorate ancestral spirits, reflecting the indigenous cosmological beliefs and social hierarchies based on clans and castes. These stone monuments, whether rough or intricately carved, symbolize the social status of their sponsors and act as vital communication tools within cultures that rely predominantly on oral traditions. The construction of these megaliths, requiring collective effort, fosters tribal cohesion and identity.

However, the rich megalithic culture of Nias and other Indonesian islands faces challenges in the modern era. Rapid cultural changes, often within mere decades, threaten the preservation of this heritage. The Indonesian constitution, Pancasila, promotes unity in diversity but does not accommodate indigenous religions considered ‘primitive,’ leading to a potential loss of this cultural legacy. The megalithic traditions of Nias Island, therefore, represent not only an architectural and historical phenomenon but also a cultural heritage that demands recognition and preservation amidst the pressures of modernity and globalization.

Historical and Cultural Overview

The earliest inhabitants of Nias were Australomelanesoid people, dating back to as early as 10,000 BC, later succeeded by Austronesian people from Taiwan. The island’s name, derived from the local word “niha” meaning “human,” reflects its rich cultural heritage. Nias has a tumultuous history, including a brief occupation during World War II by an unrecognized Nazi state proclaimed by escaped German prisoners. The island has also been significantly impacted by natural disasters, notably the 2004 Indian Ocean earthquake and tsunami, and the 2005 Nias–Simeulue earthquake, which resulted in substantial loss of life and displacement. Despite these challenges, Nias has preserved a unique culture, known for its Megalithic traditions, war dances, and the stone jumping manhood ritual. The predominant religion is Protestant Christianity, though traditional beliefs remain influential. Nias’s distinct culture is also evident in its Omo Hada houses, built on massive ironwood pillars for defense and earthquake resilience.

Grujugan

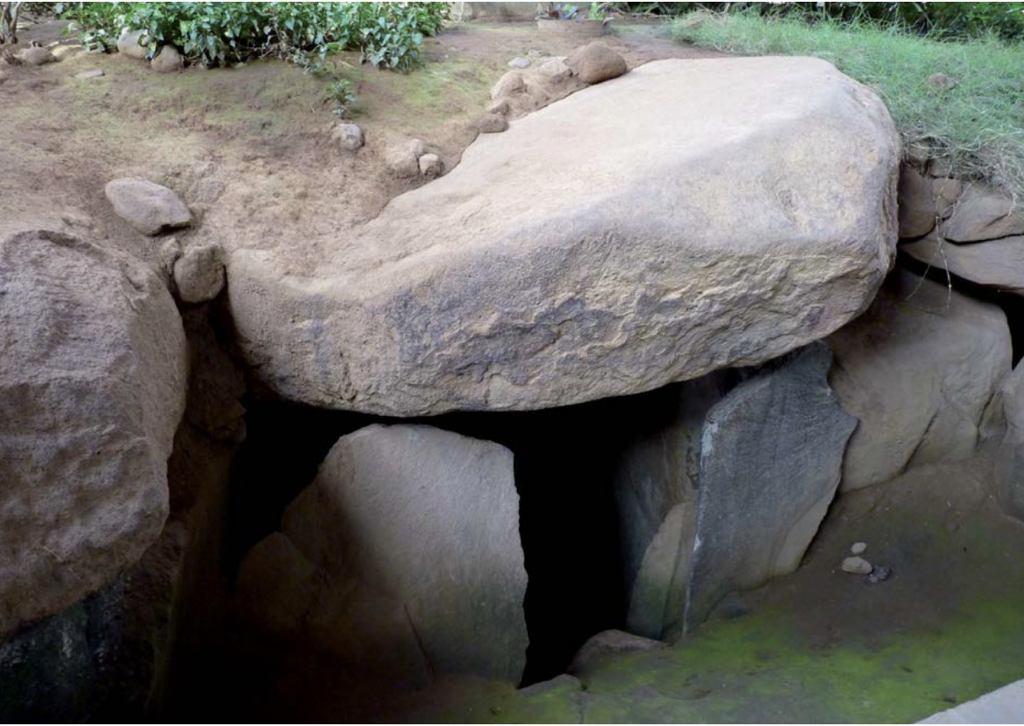

Grujugan in the Bondowoso Valley serves as a pivotal point of interest for those captivated by Indonesia’s megalithic heritage. This site is notably praised for its dolmens, known locally as “Pandhusa,” and sarcophagus cylinders, which collectively paint a picture of the spiritual and ceremonial undertakings of ancient civilizations that once flourished in this region.

The dolmens at Grujugan, characterized by their large stone compositions, evoke a sense of wonder regarding their construction and purpose. Historically, such structures have been interpreted as tombs or altars, suggesting a complex societal relationship with death and the divine. The presence of sarcophagus cylinders, some found overturned and others intricately placed in the midst of corn fields, further accentuates the ritualistic aspects tied to these megalithic forms. These artifacts, with their unique structural designs and placements, offer a glimpse into the elaborate funerary practices that defined the cultural ethos of the time.

Gunung Padang

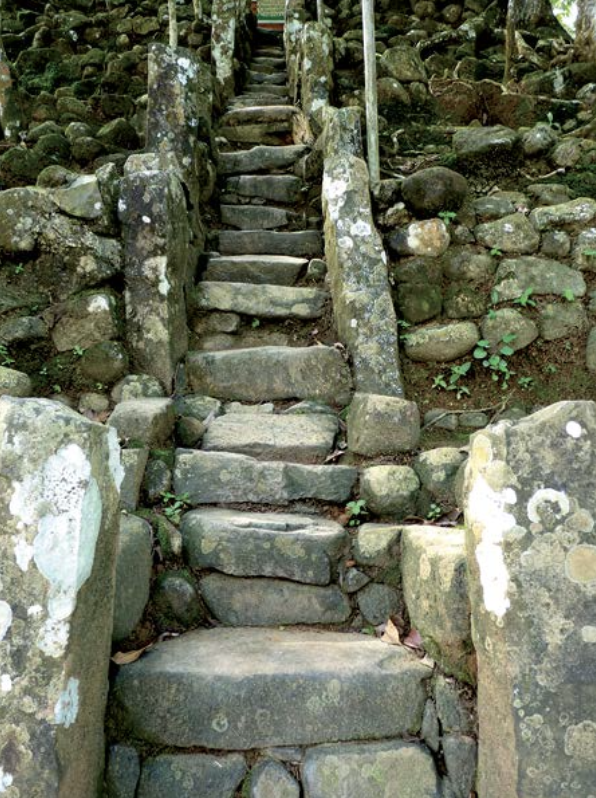

Gunung Padang emerges as a crown jewel among the megalithic sites in Sukabumi, known extensively for its cascading terraces and enigmatic rectangular structures. Often hailed as a significant archaeological marvel, the site boasts a layered complexity with terraces that elevate towards the sky, each layer narrating a different epoch of construction and use. The presence of stone prisms scattered across its slopes, monumental stone steps that guide visitors towards its zenith, and the retaining walls that preserve its terraces all attribute to Gunung Padang’s distinction as a marvel of ancient engineering and cultural significance.

The rectangular structures, notable for their deliberate architectural design, draw attention to the sophisticated planning and community effort that must have been indispensable in their creation. These edifices, potentially serving ceremonial or communal purposes, offer a tangible link to the beliefs and rituals of the societies that once thrived here, inviting ongoing exploration into their origins and functions.

Tugu Gede

Tugu Gede presents yet another fascinating chapter in Sukabumi’s megalithic narrative, featuring an arrangement of standing stones and stone seats that hint at the ritualistic importance of the site. The standing stones, with their imposing stature, are believed to have served as markers or memorials, embodying the spiritual nuances of the community. Meanwhile, the stone seats found in the vicinity suggest gatherings or ceremonies, possibly providing a space for communal or religious practices.

Moreover, Tugu Gede’s stones are enveloped in a cloak of spiritual significance, often associated with offerings for the spirits, indicating a deep-rooted connection between the physical and metaphysical realms in the lives of its creators.

Pangguyangan

Pangguyangan, known primarily for its pyramidal platform also has an array of statues that adorn its landscape. This site captures the essence of megalithic craftsmanship, with its carefully constructed pyramidal platform offering a panoramic view that harmonizes with the natural contours of Mount Halimun.

The methodical arrangement of steps leading to the platform and the meticulously designed retaining walls speak volumes of the architectural prowess and aesthetic sensibilities of its builders. Moreover, the statues, serving both decorative and symbolic roles, enrich our understanding of the cultural and religious paradigms that shaped the identity of the region’s ancient inhabitants.

Cipari

The megalithic site of Cipari in the Kuningan region is a fascinating showcase of ancient creativity and ingenuity, distinguished by its remarkable cists, as well as circle and oval structures. These formations provide invaluable glimpses into the ceremonial and possibly astronomical inclinations of the ancient communities that constructed them.

Cists, or stone coffins, discovered within the site point towards sophisticated burial practices, indicative of beliefs surrounding death and the afterlife. The meticulous arrangement of these cists, coupled with the presence of circle and oval-shaped earthworks, suggests a society deeply attuned to ritualistic practices and perhaps the cyclical nature of life and seasons. These geometrically significant structures might have served not only as burial sites but also as spaces for ceremonial gatherings or astronomical observations, highlighting the community’s advanced understanding of their environment.

Kadugede

A short distance from Cipari, the site of Kadugede presents another intriguing facet of Kuningan’s megalithic heritage through the presence of a notable cow statue. This singular piece stands as a potent symbol of the cultural and religious values that permeated the society responsible for its creation.

In many ancient civilizations, the cow was revered as a symbol of fertility, abundance, and maternal attributes, pointing to its significance in agricultural practices and societal welfare. The erection of such a statue in Kadugede could signify the community’s reverence for these ideals, transcending mere artistic expression to embody the spiritual and practical ethos of its people.

The site’s focus on a singular statue, unlike the more communal arrangements of cists and stone circles found in Cipari, showcases the diversity within Kuningan’s megalithic culture. It reflects the different facets of life and belief systems that were celebrated and venerated by its ancient inhabitants.

Tegurwangi and Belumai

The Pasemah plateau, with its sites of Tegurwangi and Belumai, captivates the observer with an impressive array of statues and dolmens. These statues, remarkable for their size and intricate craftsmanship, depict a variety of figures, embodying the spiritual and societal values of their creators. Similarly, the dolmens—table-like stone structures—suggest the plateau was a significant ceremonial center, likely associated with burial rites or rituals of ancestral veneration. The vivid imagery and monumental stone works point to a sophisticated society that valued symbolic representation and had mastered the art of stone construction.

Kota Raya

Within this rich tapestry of megalithic culture, Kota Raya emerges with its unique statues, contributing another layer to our understanding of the region’s prehistoric artistry. The distinctiveness of these statues, in form and depiction, suggests a nuanced approach to representation, possibly reflecting the diversity in spiritual beliefs or social hierarchies within the community.

Gunung Megang and Tanjung Arau

Further exploring the plateau’s mystique, Gunung Megang and Tanjung Arau offer an exquisite collection of dolmens and bas-reliefs. These bas-reliefs, with their detailed carvings of human and animal figures, provide a vivid gateway into the cosmological perceptions and daily life of the ancient inhabitants, unveiling a world where nature, humanity, and the divine intertwined. The presence of dolmens, alongside these detailed carvings, highlights the significance of these sites as focal points of cultural and spiritual activity.

Ustano Rajo Alam

Transitioning to the Minangkabau region, Ustano Rajo Alam stands out for its arrangement of stone seats and standing stones. This configuration, possibly indicative of social gatherings or judicial proceedings, underscores the communal aspect of megalithic culture, illuminating the social dynamics and organizational structures of past societies.

Guguk and Balubus

In the same vein, the sites of Guguk and Balubus in Minangkabau distinguish themselves through standing stones adorned with intricate carvings. These carvings, rich in symbolism and detail, serve as a narrative medium, etching the beliefs, myths, and possibly the genealogies of the ancient Minangkabau people into the very landscape they inhabited.

Bada Valley Megaliths

Among the highlands of Sulawesi, Bada Valley emerges as a repository of ancient heritage, home to an impressive collection of megalithic statues. Sites such as Palindo, Maturu, Langke Bulawa, and Loga in Bada Valley are celebrated for their colossal stone figures, which are emblematic of the valley’s deep-seated cultural and historical significance. These statues, ranging in form and size, create an open-air gallery that invites speculation about their origins, the societies that crafted them, and the purposes they served.

The statue of Palindo, distinguished by its size and detailed facial expressions, stands as a silent guardian of the valley’s past. Similarly, the statues at Maturu, Langke Bulawa, and Loga each contribute to the mosaic of megalithic artistry in Bada Valley, showcasing varied styles and motifs that hint at the rich cultural tapestry of their creators. Beyond their aesthetic appeal, these statues likely held profound spiritual and social significance, possibly representing deities, ancestors, or important community figures.

Besoa Valley

Transitioning to Besoa Valley, the narrative continues with statues such as Tinoe-Badang Kaya. These statues carry forth the tradition of megalithic craftsmanship found in Bada Valley, while also weaving their own unique strands into the region’s historical fabric. Tinoe-Badang Kaya, among others in Besoa Valley, underscores the diversity and depth of megalithic art forms across Sulawesi, reflecting the practices and beliefs of a bygone era.

The statues in Besoa Valley, much like those in Bada, stand as monumental testaments to the engineering skills and spiritual worldview of their creators. Their placement within the valley, often surrounded by lush landscapes, further accentuates their mystical aura, offering a window into the symbiotic relationship between the ancient people of Lore Lindu and their natural environment.

Pokekea

As a vivid expression of prehistoric creativity and spirituality, Pokekea, nestled within Besoa Valley, captivates with its monumental jars, traditionally known as Kalamba, and an array of statues that offer glimpses into the enigmatic past of this region. The array and intricacy of the artifacts found here underline the significance of this site as a cultural and religious focal point for ancient communities.

The Kalamba jars at Pokekea

The Kalamba jars discovered in Pokekea are emblematic of the region’s megalithic tradition, showcasing not just the functional aspect of container-making but also representing a spiritual or ceremonial purpose that these objects likely served. Excavations conducted in the early 2000s unveiled these jars, along with traditional houses, illustrating a society that was deeply intertwined with both the metaphysical and the material world.

A detailed exploration into the artistic embellishments on these jars reveals a complex tapestry of faces and figures, carved directly onto the surface of the stone. These decorative elements, particularly striking in the monumental jar discovered, showcase a sophistication in art and a depth of cultural expression that speaks volumes of the artisans behind them. The detailed strip of faces found on one such jar perhaps symbolized communal identities or ancestral lineages, serving as an enduring testament to the beliefs and values of the societies that thrived in Pokekea.

Glinseran

In the valleys of Bondowoso, East Java, the site is renowned for its significant presence of sarcophagus cylinders, Glinseran provides a profound insight into the spiritual and ceremonial aspects of the region’s prehistoric inhabitants.

The sarcophagus cylinders of Glinseran, imposing in their size and scattered amidst the rice fields and corn, catch the eye with their remarkable form – huge stone cylinders covering underground chambers. These sarcophagi, as unearthed in the studies and excavation efforts, hint at a complex funerary practice amongst the peoples of ancient Bondowoso. Distinctive for their lids, these sarcophagi are emblematic of the region’s megalithic tradition, showcasing not just a mastery over stone but also a deep-rooted reverence for the dead.

Bondokodi village

Olayama Village Megaliths

Olayama village, located in the Lölöwau sub-district, is home to three significant megalithic sites that contribute to our understanding of prehistoric cultures in the region. Among these, the Bitaha site stands out as the most intriguing, followed by Hilibadalu and Hili’ana’a. Historically, the Olayama region was distinguished by its unique architectural style, characterized by houses constructed on stone rather than wooden pillars. This distinctive feature underscores the cultural and historical importance of the area, providing insights into the architectural preferences and environmental adaptations of its past inhabitants.

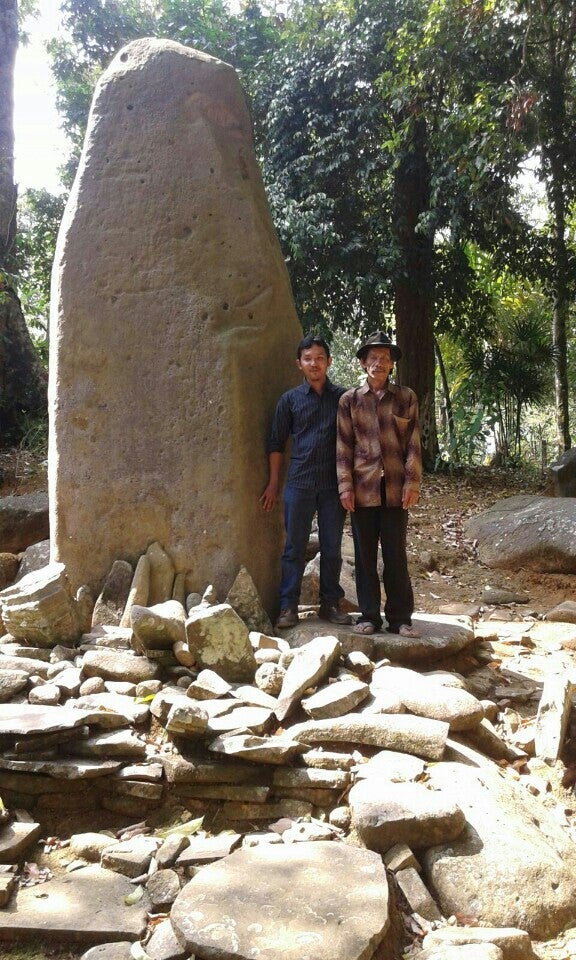

The Bitaha Megalithic Site, situated approximately 55 kilometers from the center of Gunungsitoli City and accessible via a 1.5-hour journey along the Central Nias route, is notable for its assembly of dolmens and menhirs. These megalithic structures are set against the backdrop of a traditional Nias house, which is uniquely oval-shaped and representative of North Nias architecture. The menhirs at this site, known as Awina, Sahuwa, and Behu, with Behu being the most prominent, vary in their degree of ornamentation. While some menhirs are uncarved, others feature carvings of faces and male genitalia, or are fully sculpted into squatting human forms. The Bitaha site’s establishment dates back to 10 generations ago and is attributed to the ancestors of the Halawa clan, one of the generational lines on Nias Island. This historical depth adds to the site’s significance, offering a window into the cultural practices and artistic expressions of the island’s early inhabitants.

Tarung Village

Tarung Village, a cultural gem nestled in the heart of West Sumba, East Nusa Tenggara, is renowned not merely for its traditional architecture and vibrant Marapu beliefs but also for its enigmatic megalithic stone monuments. These ancient stones, scattered thoughtfully throughout the village, stand as silent guardians of history, bearing witness to the deep spiritual and cultural roots of the Sumbanese people.

Kampung Pasunga village

Kampung Pasunga stands as a living museum, showcasing the profound symbiosis between the community’s cultural ethos and megalithic traditions. This village, adorned with traditional architecture and spangled with an array of megalithic tombstones, monuments, and village layouts, offers a unique lens into the storied past of the Sumba community, a narrative deeply intertwined with Marapu – the ancestral belief system guiding their way of life.

Central to Kampung Pasunga’s cultural landscape are the megalithic tombstones, arranged with deliberate purpose and imbued with symbols of social status. These stone monuments, varying in shapes, sizes, and adornments, serve not merely as burial sites but as vestiges of the community’s enduring reverence for their ancestors. The elaborate arrangements of these tombstones, often resembling dolmens or menhirs, reflect the hierarchical stratifications within the society, with each feature etched into the stone narrating a tale of lineage, valor, and communal identity.

Even more Megaliths

Lolomoyo village

Ononamolo

Sisarahili village

Sisarahili village is home to three traditional houses, and in its vicinity, it features captivating megalithic sites known as Tekhemböwö and Hiligoe.

Lölözirugi village

Tuhemberua village

Tuhemberua village boasts a significant anthropomorphic megalith located at the Hilimbaruzö I site.

Hiliserangkai village

Lahusa Fau village

Lahusa Fau village is distinguished by its 65 traditional houses, located just a few kilometers beyond Bawömataluo at the terminus of a slender road.

Tetegewo megalithic site

The Tetegewo Megalithic Site, located in Hisao’oto Village within the Sidua’ori District of South Nias, represents one of the most significant archaeological finds in the region. Situated atop a steep hill, this site is distinguished by its nearly 100 megaliths of various types, making it arguably the most impressive megalithic site in all of Nias

Hilinamö Zaoa village

Bawömataluo village

Numerous scholars concur that the traditional houses on Nias, known as Omo Hada, stand as premier illustrations of vernacular architecture throughout Asia. Constructed without nails, these structures demonstrate remarkable resilience to severe earthquakes, surpassing modern homes in durability. Designed with elevation from the ground for defensive purposes, Nias houses reflect the island’s history of constant conflict among its villages. The island showcases three distinct architectural styles, highlighting its rich cultural diversity.

WOW!!! I really would like to go there…. I am quite fascinated

These monoliths are similar to the ones found in the state of Meghalaya in India