Introduction to the Dresden Codex

The Dresden Codex is a significant Maya book, once considered the oldest surviving book from the Americas, dating back to the 11th or 12th century AD. However, in September 2018, it was established that the Maya Codex of Mexico, formerly known as the Grolier Codex, predates it by about a century. Rediscovered in Dresden, Germany, the codex is now housed in the museum of the Saxon State Library.

Get your dose of History via Email

Contents and Structure

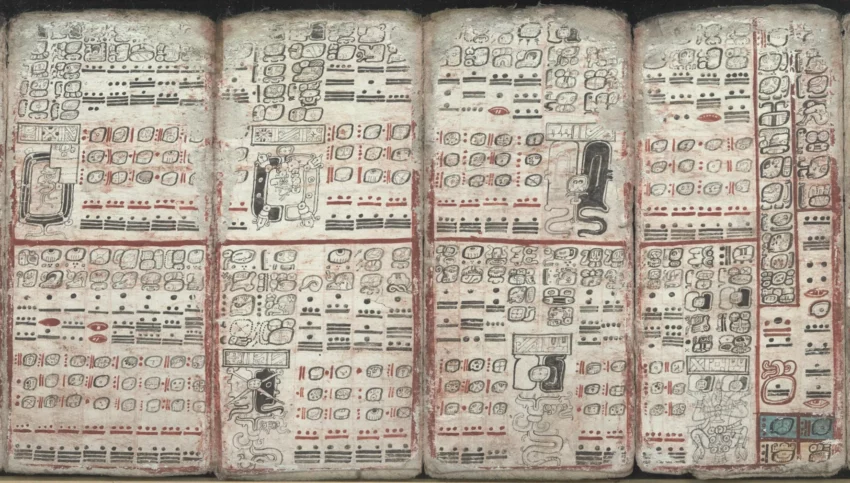

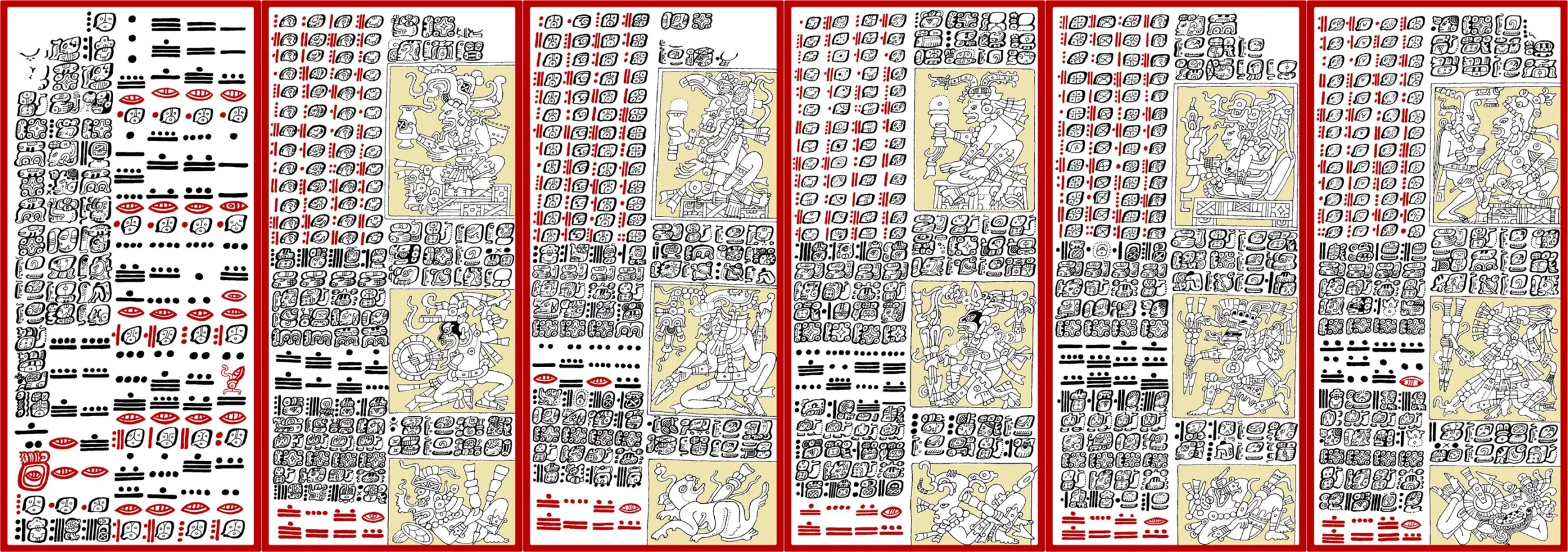

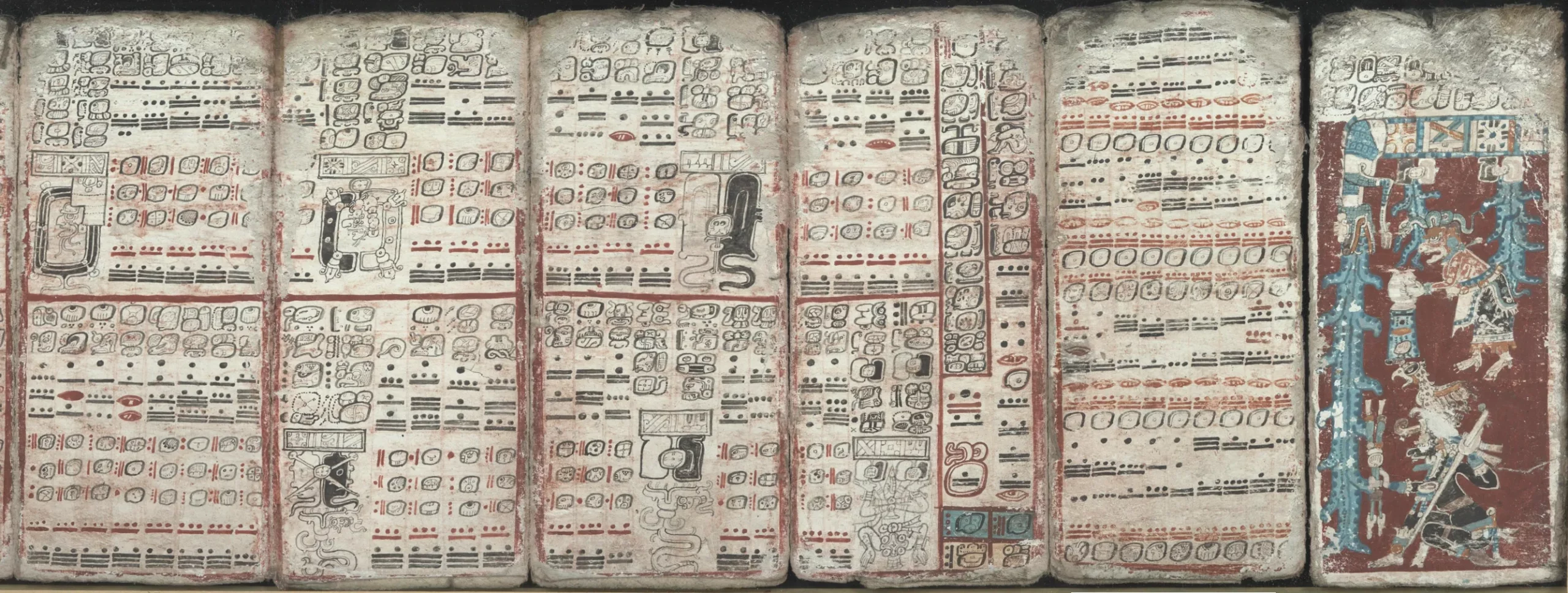

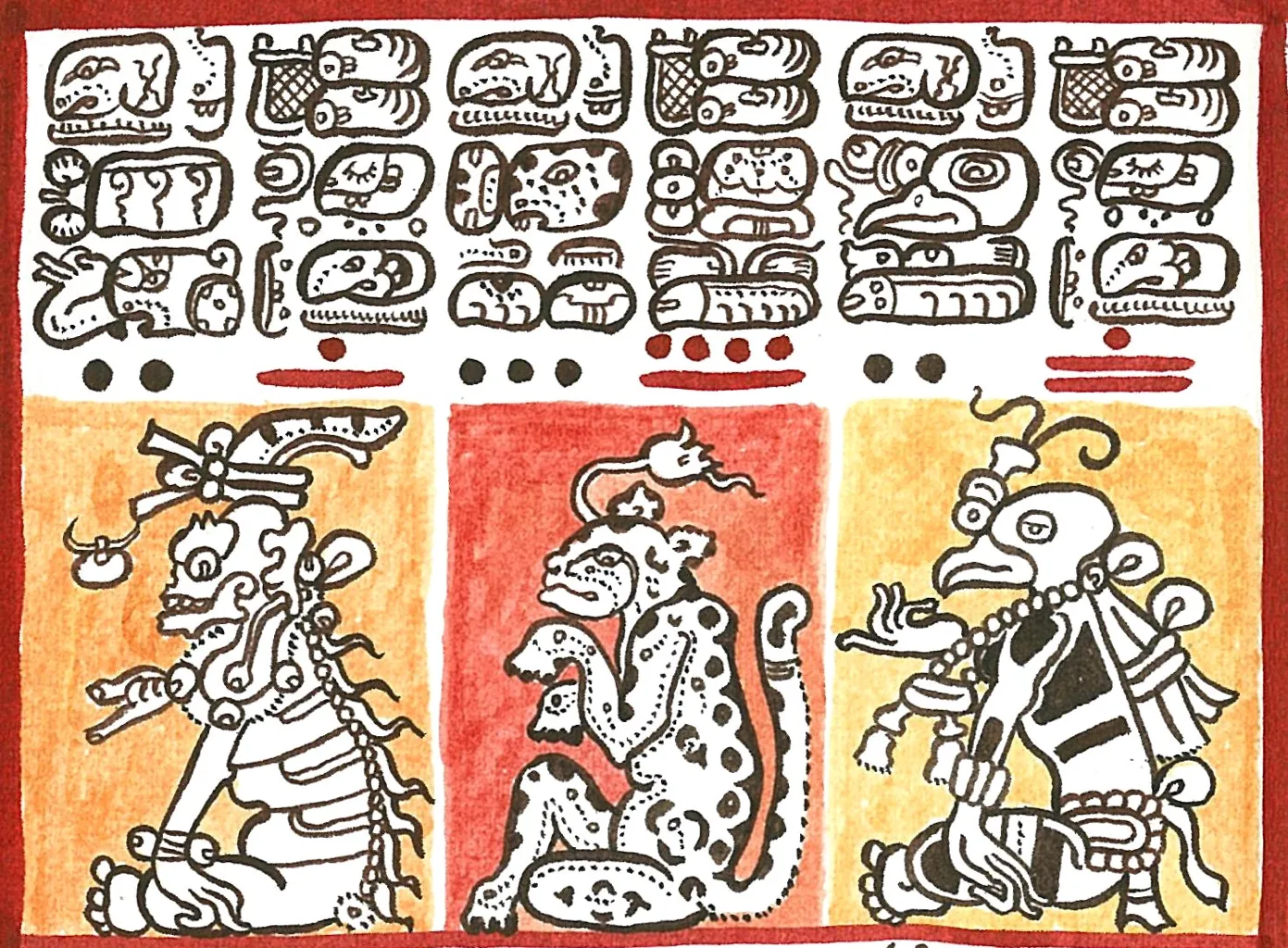

The Dresden Codex contains 78 pages with decorative board covers on the front and back. Most pages have writing on both sides, bordered by red paint, although many have lost this framing due to age. The pages are generally divided into three sections, labeled a, b, and c. Some pages have two horizontal sections, while others have up to five. The individual sections, each with its own theme, are separated by a red vertical line and are generally divided into two to four columns.

Material and Form

The pages of the codex are made of amate, a type of paper produced from the inner bark of a wild species of Ficus. The pages measure 20 centimeters high and can be folded accordion-style. When unfolded, the codex is 3.7 meters long. Written in Mayan hieroglyphs, the codex refers to an original text from three or four hundred years earlier, describing local history and astronomical tables.

Historical Significance

The Dresden Codex is one of four hieroglyphic Maya codices that survived the Spanish Inquisition in the New World. The other three are the Madrid, Paris, and Grolier codices. The Dresden Codex is held by the Saxon State and University Library Dresden (SLUB Dresden) in Germany. The pages of these codices are similar in size, with a height of about 20 centimeters and a width of 10 centimeters.

Artistic and Astronomical Content

The pictures and glyphs in the codex were painted by skilled craftsmen using thin brushes and vegetable dyes. Black and red were the main colors used, with some pages featuring detailed backgrounds in shades of yellow, green, and Mayan blue. The codex was written by eight different scribes, each with their own writing style, glyph designs, and subject matter.

Rediscovery and Publication

Johann Christian Götze, a German theologian and director of the Royal Library at Dresden, purchased the codex from a private owner in Vienna in 1739. The codex was cataloged into the Royal Library of Dresden in 1744. Alexander von Humboldt published pages from the Dresden Codex in his 1810 atlas, marking the first reproduction of any of its pages. The first complete copy of the codex was published by Lord Kingsborough in his 1831 work, “Antiquities of Mexico.”

Deciphering the Codex

The Dresden Codex has played a key role in the deciphering of Mayan hieroglyphs. Ernst Wilhelm Förstemann, a Dresden librarian, published the first complete facsimile in 1880 and deciphered the calendar section of the codex. In the 1950s, Yuri Knorozov used a phonetic approach based on the De Landa alphabet for decoding the codex, which was further developed by other scholars in the 1980s.

Astronomical Tables and Rituals

The codex contains accurate astronomical tables, including detailed Venus and lunar tables. The lunar series correlates with eclipses, while the Venus tables track the movements of Venus. The codex also includes astrological tables and ritual schedules, showing important Maya royal events in a 260-day ritual calendar. The rain god Chaac is represented 134 times in the codex.

Damage and Preservation

The Dresden Codex suffered significant water damage during World War II. Pages 2, 4, 24, 28, 34, 38, 71, and 72 were particularly affected. The damage is evident when comparing the current codex to earlier copies. Today’s page numbers were assigned by Agostino Aglio, who first transcribed the manuscript in 1825-26. Historians now understand that the codex should be read in a sequence that traverses the complete front side followed by the complete back side of the manuscript.

Conclusion

The Dresden Codex remains a vital artifact for understanding Maya civilization. Its detailed astronomical tables, religious references, and historical content provide invaluable insights into the Maya world. Despite the damage it has suffered, the codex continues to be a key resource for scholars and historians.