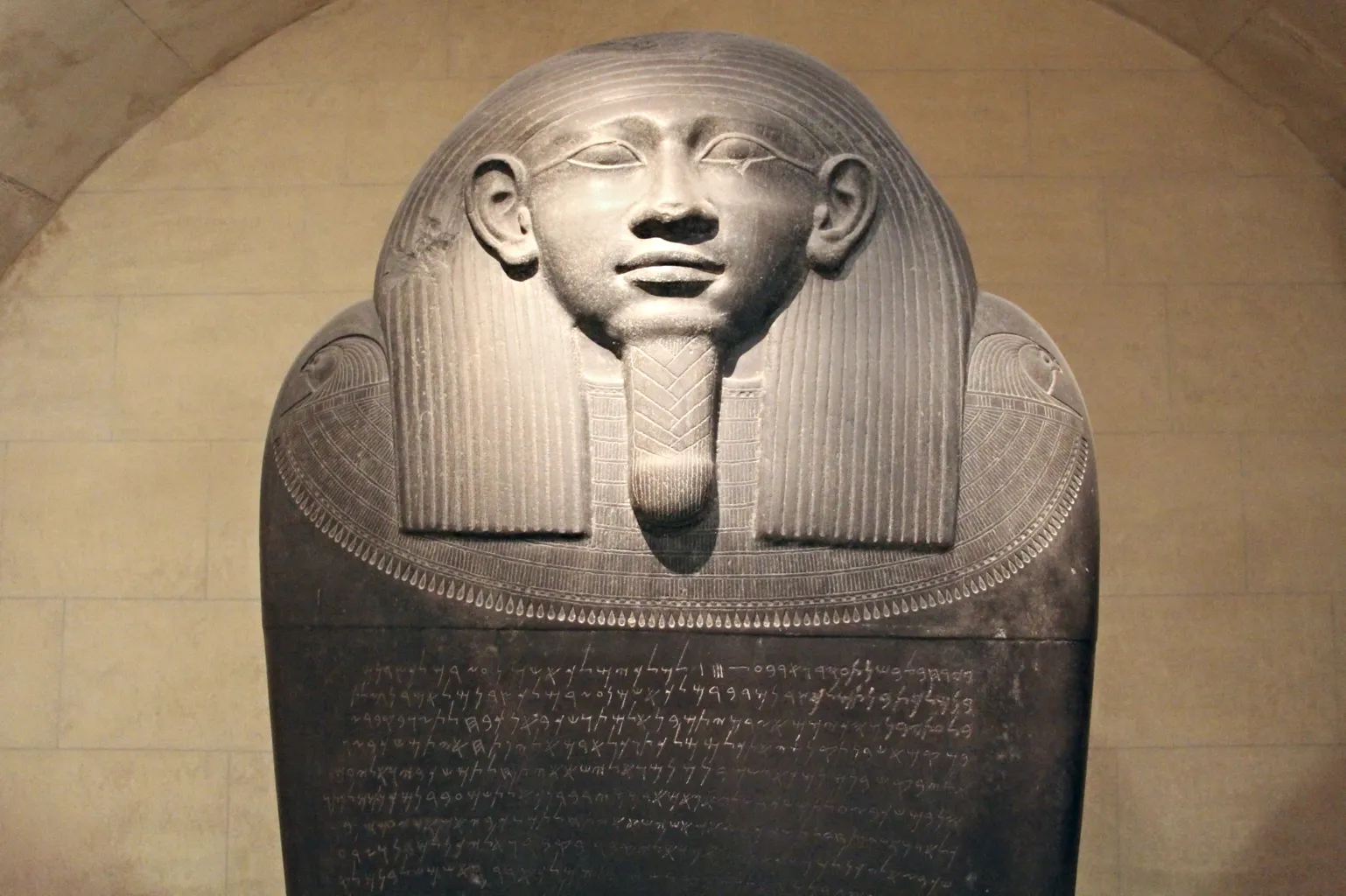

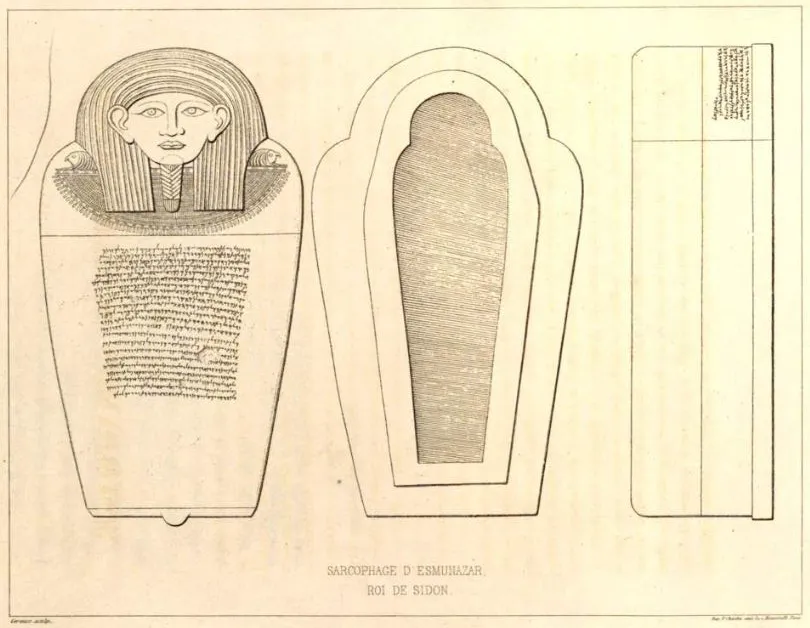

The Fascinating Tale of Eshmunazar II’s Sarcophagus

In 1855, workers unearthed an incredible find southeast of Sidon, Lebanon. They discovered the sarcophagus of Eshmunazar II, a Phoenician king from the 6th century BC. This sarcophagus stands out because it’s one of only three Ancient Egyptian sarcophagi found outside Egypt. The other two belong to his father, King Tabnit, and a woman, likely his mother, Queen Amoashtart. The Sidonians probably captured these during their involvement in Cambyses II’s conquest of Egypt in 525 BC.

Get your dose of History via Email

A Monument of Linguistic Significance

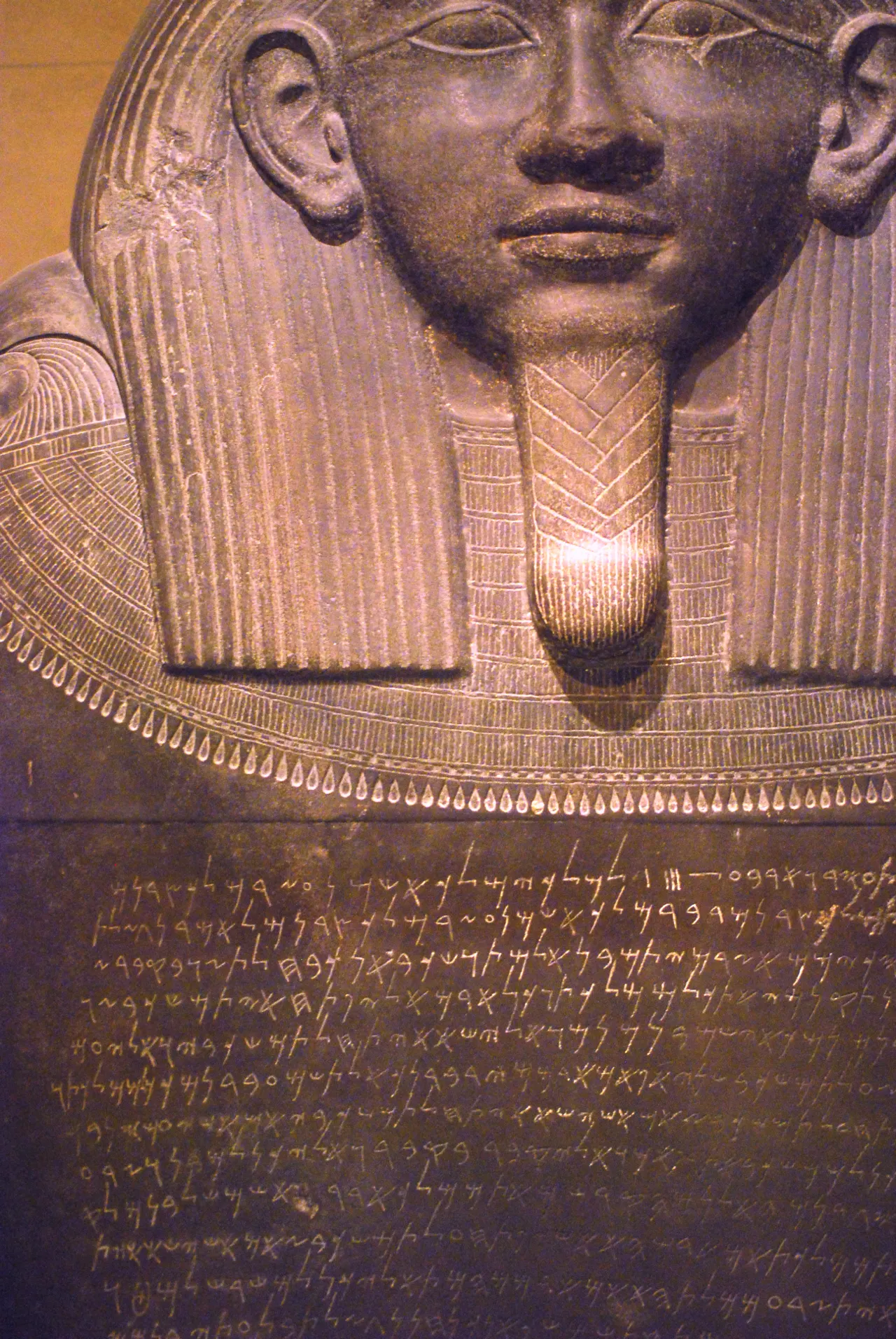

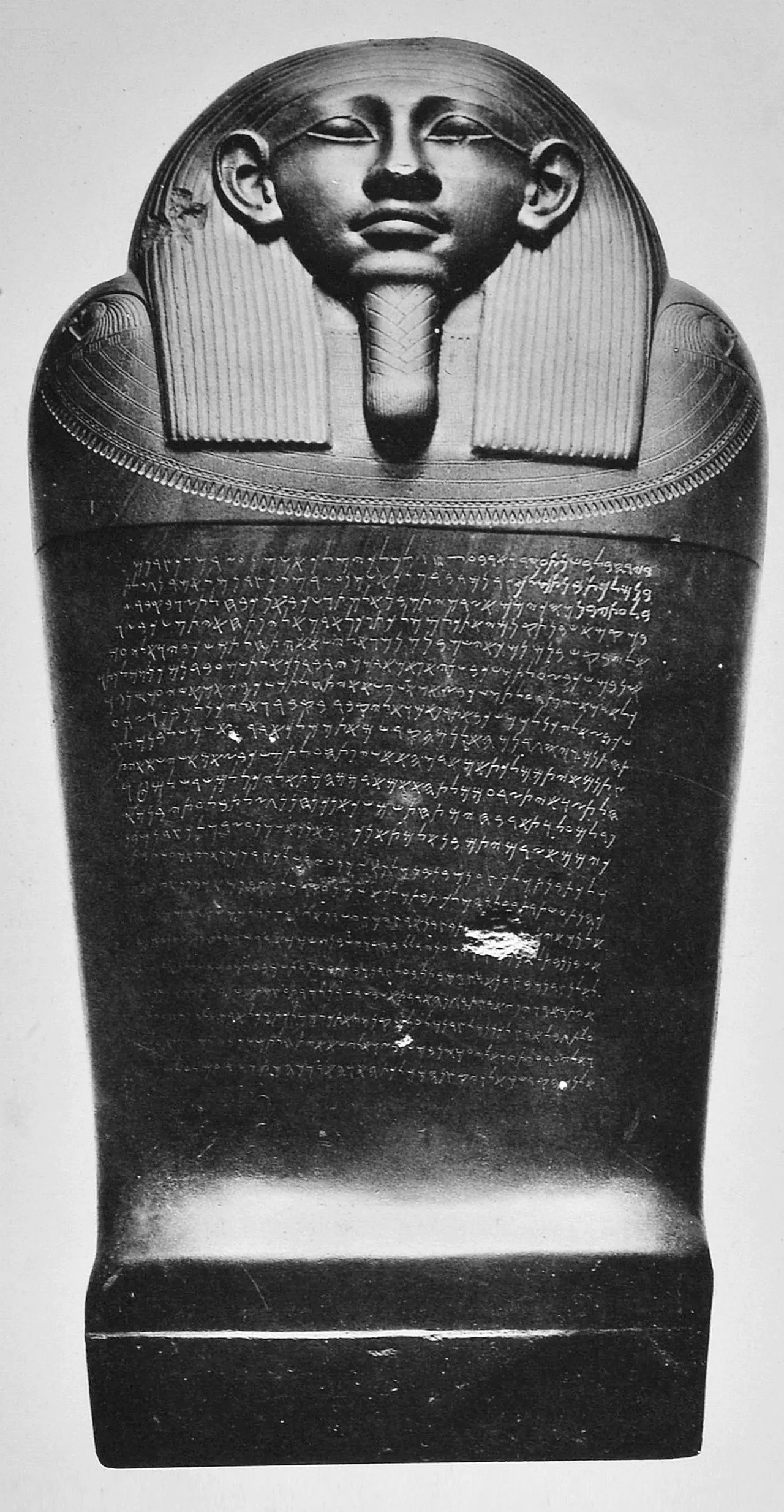

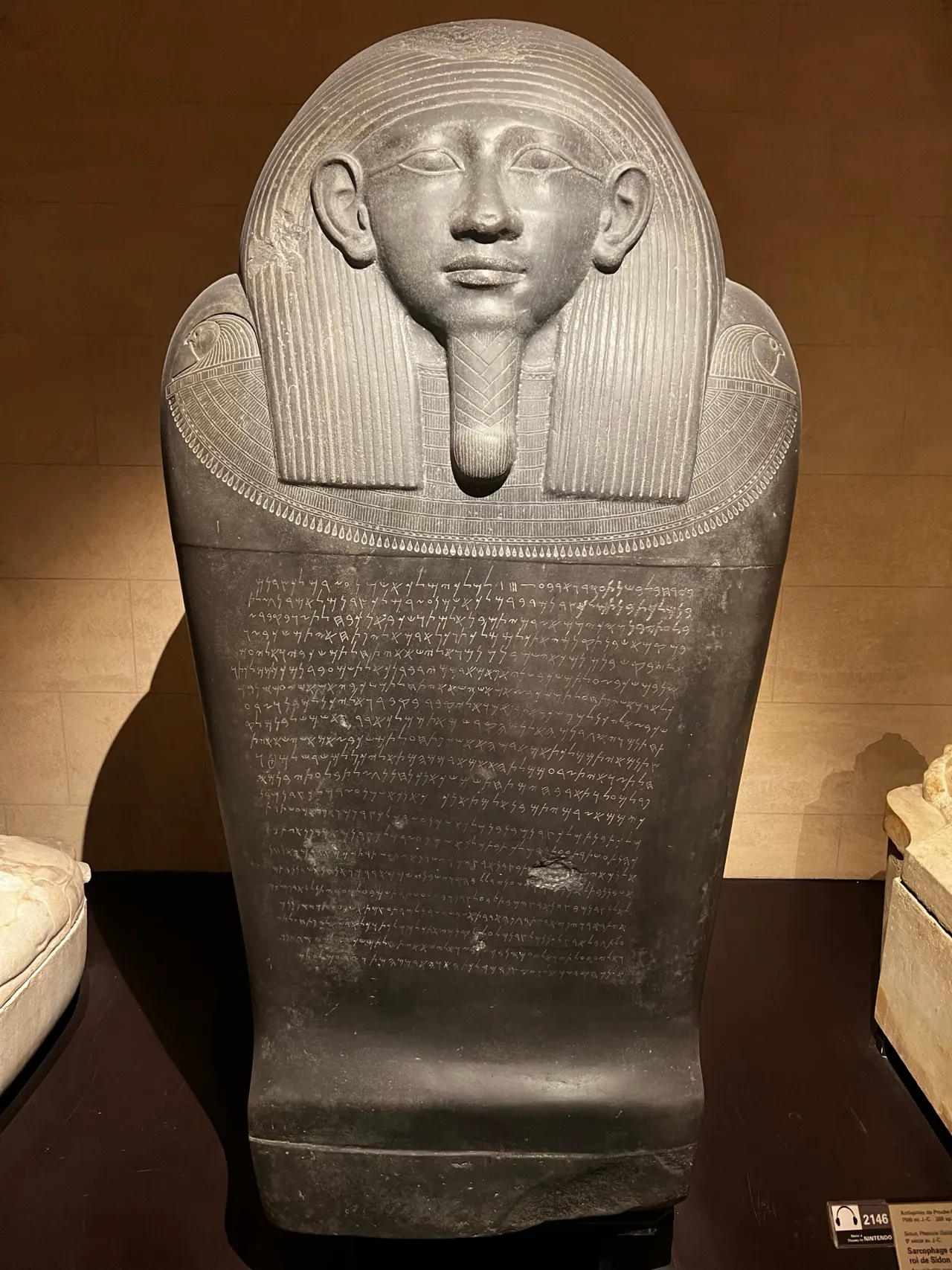

The sarcophagus has two sets of Phoenician inscriptions, one on the lid and a partial copy on the sarcophagus trough. The lid inscription was groundbreaking upon its discovery. It was the first Phoenician language inscription found in Phoenicia proper and the most detailed ever found anywhere at that time. Today, it remains the second longest extant Phoenician inscription, after the Karatepe bilingual.

The Path to the Louvre

Alphonse Durighello, a diplomatic agent in Sidon, discovered the sarcophagus. He worked for Aimé Péretié, the chancellor of the French consulate in Beirut. The sarcophagus was eventually sold to Honoré de Luynes, a French nobleman and scholar. Following a legal dispute over its ownership, it was moved to the Louvre. The discovery spurred a wave of archaeological interest in the region, leading to Renan’s 1860–1861 Mission de Phénicie, the first major archaeological mission to Lebanon and Syria.

Eshmunazar II: The Young King

Eshmunazar II reigned from around 539 BC to 525 BC. He succeeded his father, Tabnit I, and his mother, Queen Amoashtart, served as regent until he reached adulthood. Unfortunately, Eshmunazar II died prematurely at age 14. Despite his short life, he, like his parents, was a priest of Astarte and contributed to temple building and religious activities.

Phoenician Funerary Practices

Phoenicians emerged as a distinct culture on the Levantine coast in the Late Bronze Age. They had diverse mortuary practices, including inhumation and cremation. Elite burials in Sidon often used sarcophagi, with inscriptions invoking deities and cursing anyone who disturbed the tomb.

Modern Discovery and Ownership Dispute

On January 19, 1855, Durighello’s men discovered the sarcophagus in a necropolis southeast of Sidon. It lay outside a rocky mound known as Magharet Abloun. Initially protected by a vault, the tomb was already robbed in antiquity. The ownership of the sarcophagus was contested by Habib Abela, the British vice-consul general in Syria. However, a commission voted in favor of Durighello.

Transporting to France

The sarcophagus was sold to Honoré de Luynes for £400 and donated to the French government. Transporting the sarcophagus to France involved a grand convoy escorted by the citizens and governor of Sidon. The sarcophagus now resides in the Louvre’s Near Eastern antiquities section.

The Inscriptions: A Window into the Past

The lid inscription consists of 22 lines, occupying a square under the sarcophagus’ usekh collar. A partial copy of this inscription is also found on the trough. The inscriptions detail the king buried inside, his lineage, his temple construction feats, and warn against disturbing his repose. They also mention that the Achaemenid king granted Eshmunazar II territories in recognition of his deeds.

Cultural Significance

The discovery of Eshmunazar II’s sarcophagus was a landmark event, shedding light on Phoenician culture and language. It also inspired further archaeological exploration in the region, highlighting the rich history of Phoenician Sidon.

Eshmunazar II’s sarcophagus remains a testament to the rich cultural and historical tapestry of ancient Phoenicia, now immortalized in the halls of the Louvre.

Sources: