Dur-Kurigalzu, a city from ancient Mesopotamia, stands as a testament to the Kassite Dynasty’s architectural prowess. Founded by King Kurigalzu I in the 14th century BC, it served as a political and religious center. The city, named after its founder, was strategically positioned between the Tigris and Euphrates rivers. Its ruins, including a ziggurat and palatial complex, provide insight into Kassite culture and influence. Excavations have unearthed artifacts that shed light on the city’s significance in ancient times.

Kassite Dynasty

The Kassite Dynasty, which ruled over Babylonia for over four centuries (c. 1595–1155 BC), represents a significant yet enigmatic period in Mesopotamian history. Emerging in the aftermath of the Hittite sack of Babylon, which marked the end of the First Dynasty of Babylon around 1595 BC, the Kassites brought stability to a region fraught with turmoil. Their origins are somewhat obscure, but they are believed to have migrated from the Zagros Mountains, east of Mesopotamia.

Under Kassite rule, Babylonia enjoyed a period of relative peace and prosperity. This era was characterized by significant architectural projects, including the construction of palaces and temples, and the restoration of cities that had been devastated by previous conflicts. The Kassites were instrumental in the revival of the Babylonian economy, fostering trade relations with neighboring regions such as Assyria, Egypt, and the Hittites.

One of the most notable rulers of the Kassite Dynasty was Kurigalzu I, who reigned in the 14th century BC. He is known for his military campaigns, as well as his efforts to rebuild and expand Babylonian cities. Kurigalzu I also established a new capital, Dur-Kurigalzu, which served as a political and cultural center. The Kassite kings were often engaged in conflicts with their neighbors, particularly the Assyrians, with whom they had fluctuating relations of peace and warfare.

The Kassites adopted much of the Babylonian culture, language, and religion, yet they also preserved their own identity. They worshipped a pantheon of gods, including the supreme god Enlil and the storm god Adad. However, they also introduced their own deities, such as Shuqamuna and Shumalia, into the Babylonian pantheon. The Kassite period is noted for its religious tolerance and the syncretism of Kassite and Babylonian deities.

Social and daily life under the Kassite Dynasty is less documented, but it is evident that they maintained the social structures and administrative systems of their Babylonian predecessors. The society was stratified, with a ruling class of nobles and a class of free citizens, alongside slaves. Agriculture remained the backbone of the economy, with barley, dates, and livestock being the primary commodities.

The Kassite Dynasty eventually came to an end around 1155 BC, when Babylonia fell to the Elamites and then to the Assyrians. The reasons for the decline of the Kassite Dynasty are not entirely clear, but it is likely that internal strife, combined with external pressures from aggressive neighbors, played a significant role.

Despite their long reign, the Kassites left behind relatively few inscriptions, making it challenging for historians to reconstruct their history in detail. However, archaeological excavations, such as those at Dur-Kurigalzu, have provided valuable insights into Kassite architecture, art, and society. The Kassite period is thus recognized as a time of cultural integration and innovation, which left a lasting impact on the history of Mesopotamia.

In conclusion, the Kassite Dynasty was a period of stability and cultural flourishing in ancient Babylonia. Through their contributions to architecture, economy, and religion, the Kassites played a crucial role in the development of Mesopotamian civilization. Despite the challenges of reconstructing their history, the legacy of the Kassite Dynasty endures as a testament to their significant role in the ancient Near East.

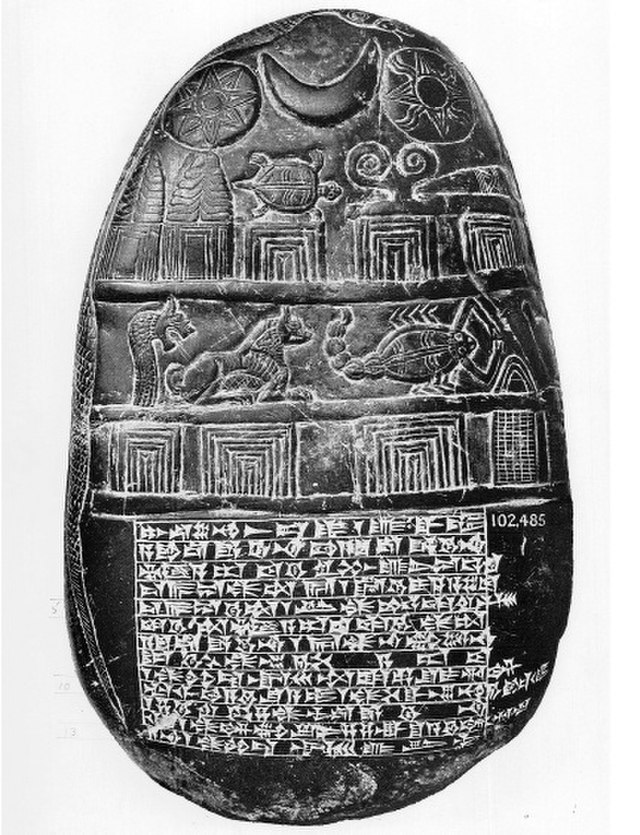

Kudurru Stones

At the crossroads of ancient civilizations, the Kudurru Stones mark a pivotal heritage of Mesopotamian society. They are not just markers of land but also a testament to the sophisticated bureaucracy and laws of the time. Intricately carved with symbols and cuneiform inscriptions, these boundary stones proclaim the power of kings and gods. They served as legal documents, detailing grants of land by the sovereign. By understanding these artifacts, we delve into the depths of ancient land rights and divine intercessions.