In the pantheon of Inca deities, Supay holds a distinctive place as the god of the underworld, also known as Uku Pacha. This realm was not only a place of the dead but also a domain of untapped resources and potential, embodying both fear and reverence in the Inca civilization. Supay’s role extended beyond the mere guardianship of the afterlife; he was also associated with minerals and the unseen forces within the earth, making him a complex figure within Inca mythology.

The Inca Empire

The Inca civilization, emerging in the early 13th century, established itself as a formidable empire in the Andes of South America, becoming the largest empire in pre-Columbian America. Known for their remarkable engineering feats, the Incas constructed extensive and sophisticated structures, roads, and terraces that harmonized with the natural landscape. Among their architectural marvels, the majestic city of Machu Picchu stands out, perched high in the mountains, captivating modern visitors with its beauty and mystery. The empire’s ability to assimilate nearby cultures into its fold led to the formation of a diverse society, all while maintaining a centralized government with the Sapa Inca at its helm, revered as a living deity. The Inca society was highly organized, boasting a robust economy primarily based on agriculture. The cultivation of potatoes and maize played a pivotal role in sustaining the population and supporting the empire’s extensive public works. Despite lacking a written language, the Incas ingeniously used a complex system of strings and knots known as quipu for record-keeping. Religion was central to Inca life, with the Sun god Inti occupying the foremost position in their pantheon.

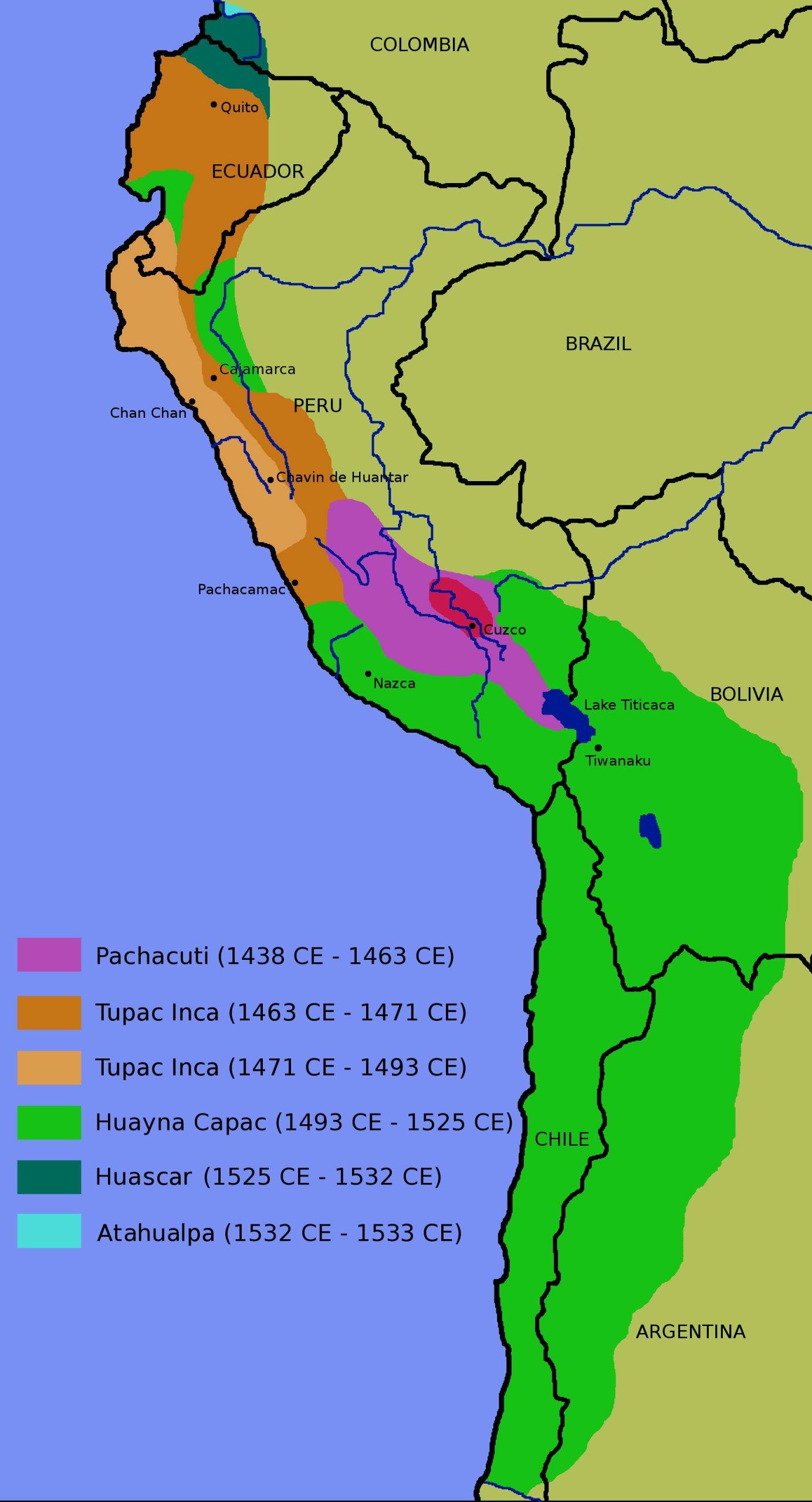

The Incas engaged in elaborate ceremonies to venerate their gods, firmly believing in an afterlife. However, the arrival of Spanish conquistadors led by Francisco Pizarro in the 16th century marked the beginning of the empire’s decline, a downfall that could not erase the enduring legacy of the Inca civilization. Strategically located in the Andes, the Inca Empire’s vast territory spanned parts of present-day Peru, Ecuador, Chile, Bolivia, and Argentina. This expansive reach allowed the Incas to harness a variety of climates and landscapes, from towering mountains to lush coastal plains, facilitating the cultivation of diverse crops to support a large populace. Cusco, the empire’s nucleus, served not only as the political center but also as the religious and cultural heart of the Inca civilization, embodying the empire’s might and spirituality. The conquest of the Inca Empire by the Spanish, led by Francisco Pizarro, stands as a pivotal moment in its history. Welcomed initially, the Spanish quickly betrayed the Incas, capturing the ruler Atahualpa in 1532. Despite a substantial ransom paid in gold and silver, Pizarro executed Atahualpa, precipitating the empire’s rapid decline. The conquest was aided by internal conflicts within the Inca Empire and the introduction of European diseases, to which the Incas had no immunity, marking the end of their dominion. Yet, the Spanish conquest could not completely extinguish the Incan influence from the region.

Central to the Inca diet was the potato, a crop native to the Andes and perfectly suited to the high-altitude cultivation. The Incas developed numerous methods to preserve and prepare potatoes, including freeze-drying them into chuño, which could be stored for extended periods. Maize was another essential crop, used to produce chicha, a fermented beverage integral to religious and social ceremonies.

Today, the descendants of the Inca people continue to inhabit the Andes, preserving their rich heritage and traditions. They speak Quechua, the language of their ancestors, which has endured through centuries despite the Spanish conquest, serving as a living connection to their illustrious past. The presence of Inca descendants in the Andes today is a testament to the resilience and enduring legacy of the Inca civilization. These modern-day Incas maintain many of their ancient customs and the Quechua language, ensuring that the spirit of their ancestors lives on. The Inca civilization, with its advanced agricultural practices, architectural achievements, and complex societal structures, remains a subject of fascination and admiration, a reminder of the ingenuity and strength of the human spirit in the face of adversity.

Explore Inca Archaeological Sites and Artifacts

History of the Inca Empire

The Inca Empire, known as Tawantinsuyu, emerged in the early 13th century from the highlands of Peru and expanded to become the largest empire in pre-Columbian America. Its growth was rapid, flourishing mainly during the 15th and early 16th centuries under the leadership of powerful rulers such as Pachacuti Inca Yupanqui, who initiated a series of conquests that vastly extended the boundaries of the Inca realm.

This civilization developed sophisticated agricultural techniques, such as terrace farming and irrigation, to sustain its population and support its expansion. The Incas were also renowned for their unique art, architecture, and a network of roads spanning over 40,000 kilometers, facilitating communication, trade, and military mobilization across diverse terrains, from the arid plains of the coast to the peaks of the Andes.

The administrative, political, and military center of the empire was located in Cusco, in modern-day Peru. The Inca Empire was a highly organized society, with a complex system of governance that integrated conquered peoples through both direct control and by fostering allegiance to the Inca state, often allowing local leaders to maintain their positions in exchange for loyalty.

Inca Society and Culture

Inca society was highly stratified, with the Sapa Inca at the apex, revered as a god-king. Below him was a hierarchy of nobles, priests, and administrators who ensured the smooth running of the empire. The majority of the population were commoners, who worked the land and served the state through a labor tax system known as mit’a, which required them to work on public works projects or serve in the military for certain periods.

The Incas did not have a written language as we understand it; instead, they used a system of knotted strings known as quipus to keep records and communicate information. This system was sophisticated enough to record numerical data and possibly even narratives, although the exact functioning of quipus remains partially understood.

Religion played a central role in Inca society, with a pantheon of gods worshiped, the most important of which was Inti, the sun god. The Incas practiced human and animal sacrifice for religious purposes, especially during significant events such as the death of a Sapa Inca or during times of famine or natural disasters.

Culturally, the Incas were accomplished engineers and architects, creating monumental structures such as Machu Picchu, which remains a symbol of their architectural ingenuity and understanding of natural landscapes. Their art, music, and literature, although not preserved in the same way as their architecture, were integral parts of their cultural expression, deeply intertwined with their religious beliefs and societal norms.

The Spanish Conquest and Its Impact

The Spanish conquest of the Inca Empire began in 1532 with the arrival of Francisco Pizarro and a small contingent of Spanish conquistadors. The empire was already weakened by a recent civil war between two sons of the previous Sapa Inca, Huayna Capac, who had died of smallpox, a disease introduced by Europeans. This internal conflict, combined with the devastating impact of European diseases to which the indigenous population had no immunity, significantly facilitated the Spanish conquest.

Pizarro captured the Inca emperor Atahualpa during the Battle of Cajamarca, demanding and receiving a vast ransom of gold and silver. Despite receiving the ransom, the Spanish executed Atahualpa, leading to further destabilization of the Inca governance structure. The Spanish conquest was marked by extreme violence and the exploitation of the indigenous population, leading to a dramatic decline in their numbers due to warfare, enslavement, and disease.

The impact of the Spanish conquest on the Inca Empire was profound. It not only led to the collapse of the Inca state but also to the significant loss of indigenous cultures, languages, and traditions. The Spanish imposed their own culture, language, and religion, fundamentally altering the social and cultural landscape of the region. However, despite the conquest, many aspects of Inca culture and knowledge have survived and continue to influence contemporary society in the Andes, testament to the resilience and ingenuity of the Inca civilization.

FAQ: Deciphering the Fall and Beliefs of the Inca Empire

What killed the Inca Empire?

The demise of the Inca Empire was not caused by a single factor but rather a combination of internal strife, European diseases, and Spanish conquest. The arrival of the Spanish conquistadors led by Francisco Pizarro in 1532 coincided with a devastating civil war between two Incan brothers, Atahualpa and Huáscar, over the throne. This internal conflict weakened the empire significantly. Moreover, diseases such as smallpox, introduced by the Europeans, decimated the Incan population, which had no immunity to such illnesses. The combination of these elements facilitated the Spanish conquest, leading to the eventual fall of the Inca Empire.

Were the Incas violent or peaceful?

The Inca Empire, like many large empires throughout history, had both violent and peaceful aspects. They were skilled warriors who expanded their territory through conquest, incorporating the cultures and peoples they conquered into their empire through a mix of diplomacy and military force. However, the Incas also focused on integrating these societies into their empire by sharing their advanced agricultural techniques, architecture, and extensive road systems. They promoted a sense of unity and cooperation among the diverse groups within their empire, which can be seen as a peaceful aspect of their rule.

How did the Inca empire fall?

The fall of the Inca Empire can be attributed to a combination of factors including internal conflict, disease, and Spanish conquest. The civil war between Atahualpa and Huáscar weakened the empire, making it vulnerable to external threats. The spread of European diseases further reduced the Incan population and their ability to resist the invaders. Finally, the Spanish, led by Francisco Pizarro, capitalized on these vulnerabilities, employing superior military tactics and forming alliances with rival indigenous groups. The capture and execution of Atahualpa in 1533 marked a significant turning point, leading to the eventual Spanish domination and the end of the Inca Empire.

What was the Inca religion?

The Inca religion was a complex polytheistic system that played a central role in the social and political life of the empire. It was deeply intertwined with astronomy, agriculture, and the Andean landscape. The Incas believed in a pantheon of gods who controlled various aspects of the natural world and human life. They practiced rituals and ceremonies to honor these deities, including human and animal sacrifices. The sun god, Inti, was particularly important, as the Inca considered their ruler to be the son of Inti. The religion also emphasized ancestor worship and believed in an afterlife.

What were the names of the Inca gods?

The Inca pantheon included numerous gods, each overseeing different aspects of the world and human existence. Some of the most significant Inca gods were:

– Inti: The sun god and the most important deity, believed to be the ancestor of the Incas.

– Viracocha: The creator god who fashioned the earth, heavens, sun, moon, and all living beings.

– Pachamama: The earth mother goddess, revered for her fertility and nurturing qualities.

– Illapa: The god of thunder, rain, and war, often depicted holding a club and stones.

– Mama Quilla: The moon goddess, considered the wife of Inti, and associated with marriage, the menstrual cycle, and the calendar.

– Supay: The god of the underworld and death, also associated with minerals and precious stones.

These gods, among others, formed the core of the Inca religious system, influencing daily life, agricultural practices, and imperial policies throughout the empire.

How Long Is the Inca Trail?

The classic Inca Trail to Machu Picchu is approximately 26 miles (42 kilometers) long. It is a multi-day hike that typically takes about four days to complete, leading trekkers through a stunning range of environments, including cloud forests and alpine tundra. The trail passes several Inca ruins along the way, culminating in the arrival at the iconic Sun Gate (Intipunku) with a breathtaking view of Machu Picchu at sunrise on the final day. There are also shorter and longer variations of the trail, catering to different levels of hiking experience and time constraints.

Why Did the Inca Engage in Continuous Expansion?

Economic and Political Motivations

The Inca Empire’s continuous expansion was driven by a combination of economic and political factors. Economically, expansion allowed the Incas to gain control over a variety of resources, from fertile agricultural lands in the valleys to mineral wealth in the mountains. Politically, expansion increased the power and prestige of the Inca ruler, solidifying his status as a divine leader and unifying the empire under a centralized administration.

Social and Religious Factors

Social and religious motivations also played a crucial role in the Inca’s expansionist policies. The Incas believed in the concept of reciprocal labor, or mit’a, which was used to mobilize large labor forces for projects like road construction and military campaigns. Expansion was seen as a way to spread the Inca culture and religion, integrating conquered peoples through a combination of coercion and assimilation. The Incas also practiced ancestor worship, and expanding the empire was a way to honor and provide for deceased ancestors.

Strategic Considerations

Strategically, the Incas expanded to secure their borders and preempt potential threats from rival states and nomadic groups. By controlling a vast territory, the Inca Empire could more effectively manage and deploy its resources in times of conflict. The establishment of a network of roads and storehouses throughout the empire also facilitated rapid communication and troop movement, further enhancing the Incas’ military capabilities.

In summary, the Inca Empire’s continuous expansion was a multifaceted strategy that served economic, political, social, religious, and strategic objectives, enabling it to become one of the largest and most powerful empires in the pre-Columbian Americas.

Mama Quilla: The Inca Moon Goddess

Mama Quilla, revered in the pantheon of Inca deities, holds a significant place as the Goddess of the Moon. She embodies the celestial embodiment of femininity, fertility, and time. As a pivotal figure in Inca mythology, Mama Quilla’s influence extends beyond the heavens, deeply intertwining with the daily lives and spiritual practices of the Inca civilization.

Illapa: The Inca God of Thunder

Illapa, revered in the pantheon of Inca deities, holds a significant place as the god of thunder, lightning, and rain. This deity, also known as Apu Illapu, Ilyap’a, or Illapa, was integral to the agricultural cycles and water management systems that were central to the Inca civilization, one of the most sophisticated societies in ancient South America. The Incas, with their capital in Cusco, worshipped a pantheon of gods, among which Illapa was particularly venerated for his control over the vital elements of weather, crucial for crop growth and water resources.

Pachamama: The Earth Mother Goddess

Pachamama, revered as the Earth Mother Goddess, holds a central place in the pantheon of Inca deities. Symbolizing fertility, agriculture, and the nurturing aspects of nature, Pachamama is a testament to the Inca civilization’s deep connection with the earth and its cycles. This goddess embodies the mountains, soil, and all elements that foster life, making her worship integral to the Inca’s agricultural practices and their understanding of the natural world.

Inti: The Inca sun god

Inti, revered as the supreme solar deity in the Inca pantheon, holds a central place in the mythology and cosmology of the Inca civilization. As the sun god, Inti was not only worshiped as the source of warmth, light, and life but also regarded as the ancestor of the Incas, reinforcing the divine right of the Inca rulers, who were considered direct descendants of Inti. This connection between the deity and the ruling class underscored the sociopolitical structure of the Inca Empire, intertwining religion with governance.

Viracocha: The Inca Creator God

Viracocha stands as a paramount figure in the pantheon of Inca mythology, revered as the supreme creator god. His influence spans the creation of the cosmos, the earth, and all living beings, marking him as a central deity in the Inca religious system. This deity’s narrative not only offers insight into the cosmological views of the Inca civilization but also reflects the broader Andean cultural traditions.